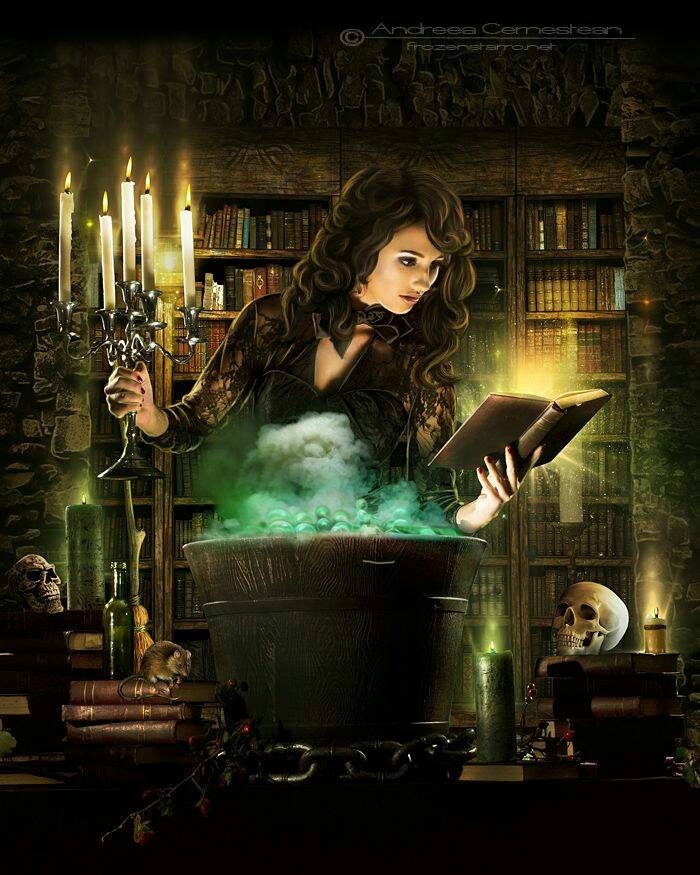

Grimoire X

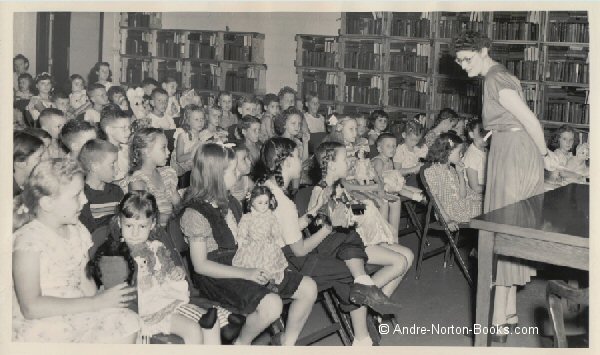

Andre the Librarian hosting "Story Time" at the Cleveland Public Library ~ 1948

"Come on In! . . .Take a Seat! . . . and Settle Down! . . ."

As the Ghost of Andre shares with you a tale by one of the leading story tellers of the past century.

Twice a Month (on the 1st and the 16th) We are going to post an original story by Andre Norton

During the showcase period you will be able to read it here free of charge.

Many were only published once.

So, it's a sure thing that there's going to be a few you have never heard of.

The order will be rather random in hopes you return often.

Happy Reading!

Nine Threads of Gold

by Andre Norton

The way along the upper sea cliff had always been the secondary road into the Hold. Erosion had left only a narrow thread of a trail, laced with ice from the touch of storm-driven waves.

It was midafternoon but there was no sun, the sullen greyness of the sky all of a piece with the cracked rock underfoot. The wayfarer leaned under the leash of a frost wind, digging the point of a staff into such crevices as would give her strength to hold when the full blasts struck.

The traveler paused, to face inland and stare at a tall pillar of rock ending in a jagged fragment pointing skyward like a broken talon. Then the staff swung up and, for a second, there was a play of bluish glimmer about that spear of rock, which vanished in a breath as if the next gust of wind had blown out a taper.

Now the path turned abruptly away from the sea. Here the footing was smoother, the way wider, as if the land had preserved more than the wave-beaten cliffs allowed. It followed for a space the edge of a valley, narrow as an arrow-point at the sea tip, widening inland. The stream that bisected the valley ran toward the sea, but where it narrowed abruptly stood a building, towered, narrow of window, twined with a second structure, a bridge connecting them, allowing the stream full passage between.

In contrast to the grey stone of the cliffs the blocks that formed the walls of those two structures were a dull green, as if painted by moss growth undisturbed by a long flow of years.

The traveler paused at the head of a steep-set stairway descending from the cliff trail, for a searching survey of what lay below. There were no signs of life. Those slits of windows were lightless, blind black eyes. The fields beyond lay fallow and now thick with tough grass.

"Sooo---" The wayfarer considered the scene. In her mind one picture fitted over another. The land she surveyed was spread with an over coating of another season, another time. And life in many forms was there.

She gathered her cloak closer at her throat and started to pick a careful way down the stair. The clouds at last broke, as they had threatened to do all that day. Rain began as a sullen drizzle, coating those narrow steps dangerously.

However, she did not halt again until she reached what had once been a wider and better-traveled way leading inward from the sea. In spite of the rain she stopped again, peering very intently at the building. Holding her staff a little free from the pavement, she swung it back and forth. No, she had not mistaken that tug. But a warning was as good as a coat of armor might be---sometimes.

Such a long time--- Seasons sped into each other in her thoughts, and she did not draw on any one memory.

The road had been well set long ago but now its pavement was akilter from the push of thick-stemmed shrubs, grey and leafless at this season. It still led straight to an arch giving on the nearer end of the bridge that united the two buildings. Down below, the stream gurgled sullenly, but the birds who had haunted the cliffs had been left behind, and there was no other sound---save now and then a roll of distant thunder. She stepped out on the bridge, her staff still held free of the pavement, the lower end pointed a little forward. If only a small portion of what she suspected was the truth, there was that which must be warded against.

Now the archway leading to the courtyard of the larger building was an open gape. Suddenly her staff swung forward at knee level.

There was a flash of blue flame, a speeding of sparks both to right and left as she took a single step on into the courtyard.

"Here entered no darkness---" She spoke that sentence aloud as if it were a charm---or password---at the same time pushing back the hood that had concealed her face, so displaying a countenance like a statue meant to honor a Queen or Goddess long forgot. While the hair wound tightly about her head was silver, there were no marks of age on her, only that calm which comes to one who has seen much, weighed much, known the pull of duty.

“Come---” Her staff moved in a small beckoning.

The two who first advanced into the open moved warily and plainly showed that they were coming against their will. There was a boy, his bony frame loosely covered with a patchwork of badly cured skins cobbled together. Both his hands were so tight about the smaller end of a club that the knuckles showed, nearly piercing the skin. But the girl was not far behind him, and she weighed in her two hands a lump of stone, jagged and large enough to be a good threat.

There was also movement from the wall behind, wherein that gate was, though the traveler made no attempt to turn or even look over her shoulder. Another boy, near as thin as the taut bowstring arming the weapon he carried, and a girl, with a dagger in hand, sprang from some perch above. A boy, also with bow in hand, joined them. The three sidled around the stranger, their weapons at ready, their faces showing that they were not ignorant of the lash of fear nor the use of the arms they carried.

Five---

“The others of you?" The traveler made a question of that.

Those arose out of hiding as if the fact that she asked drew them into sight. Two boys, twins, so alike that one might be the shadow of the other, each armed with a spear of wood, the points of which had been hardened by careful fire charring and rubbing. Another girl, who had no weapon, but carried a younger child balanced on her hip.

Nine. In so much--- Yet this was not what she had expected. The traveler looked intently from one gaunt face to the next. No, not what she had expected. But in a time of need a weaver must make do with the best there is to hand.

It was the eldest of the boys, he who had leaped first from the wall, who gave challenge. He was of an age to have been a squire, and he wore a much too large and rusty coat of mail, a belt with an empty sword scabbard bound about it to hold it to his body.

"Who are you?" His demand was sharp and there were traces of the old high tongue in the inflection of his speech. "How came you here?"

'She came the sea path---" It was the girl who had lain in hiding with him on the upper wall who spoke then, and her dagger remained unsheathed. However, it was the younger one who carried the baby who spoke, her gaze holding full upon the traveler:

"Do you not see, Hurten, she is one of Them.”

They stood in a semicircle about the woman. She could taste fear, yes, but also with that something else, the grim determination that had brought them to this ancient refuge, kept them alive when others had died. They would be stout for the weaving, these nine threads distilled from a broken and ravaged land.

"l am a seeker," the woman answered. "If I must answer to a name let it be Lethe."

"One of Them,” repeated she who played nursemaid, stubbornly.

The boy Hurten laughed, "Alana, They are long gone. You see tales in all about you. Lethe---" He hesitated, and then with now more than a touch of the courtly tongue, "Lady, there is nothing here---" Still holding bow, he spread his hands wide apart, as if to encompass all that lay about him. "We mean no harm. We can spare you a place by a fire, a measure of a roof against the storm---little more. We have long been but wayfarers also."

I.ethe raised her head so that the folds of her hood slid even farther back.

"For your courtesy of roof and hearth, I give thanks. For the goodwill that prompted such offers, may that be returned to you a hundredfold.”

Alana had allowed the small boy in her arms to wriggle to the ground. Now, before she could seize him back in a protective hold, he trotted forward, one hand outstretched to catch full hold on Lethe's cloak, supporting himself as he looked up into her face.

' 'Maman?" But even as he asked that his small face twisted and he let out a Cry. “No---maman---no, maman!”

Alana swooped to catch him up again and Lethe spoke to her softly: "This one is of your blood kin?"

The girl nodded. "Robar, my brother. He . . . doesn't understand, lady. We were with a pilgrim party. The demons caught us by a bridge. Maman, she told me to jump and she threw Robar down to me. We hid in the reeds--- He--he didn't see her again."

"But you did?"

For a moment there was stark horror in Alana's eyes. Her lips formed a word she did not appear to have the strength to voice. Lethe's staff raised; the point of it touched ever so lightly on the little girl's tangle of hair.

"Fade," the woman said, "let memory fade, child. There will come a balancing in good time. Now," she spoke to Hurten, "young sir, I am right ready to make acquaintance of this promised fire and roof of yours.”

It would seem that any suspicion they had held was already eased. The weapons were no longer tightly in hand, though the children still surrounded her in a body as she walked ahead, well knowing where she was bound, through the doorway that led into the great presence chamber.

Outside the day was fast darkening into twilight; herein there was light of a sort. Globes set in the walls gave off a faint glimmer as if that which energized them was close to the end of its power. What this dim radiance showed was shadow-cloaked decay.

Once there had been strips of weaving along the walls. Now there were webs of dwindling threads from which all but the faintest of patterns had been lost. There was a dais on which had stood an impressive line of chairs, tall-backed, carven. Most of those had been hacked apart and, as they passed, the children each went forward and picked up an armload of the broken wood, even small Robar taking up one chunk, as if this were a duty to which all of them were sworn.

They passed beyond a carven screen through another door and down a hall until they came into another chamber, which gave evidence of being a camping place. Here was a mighty cavern of a fireplace wherein was hung a pot nearly large enough to engulf Robar himself, and about it other tools of cookery.

A long table, some stools, had survived. Near the hearth to one side was a line of pallets fashioned from the remains of cloaks, patched with small skins, and apparently lumpily stuffed with what might be leaves or grass.

There was a fire on the hearth, and to that one of the twins added wood from the pile where they had dumped their loads, while the other stirred the sullen glow within to greater life.

Hurten, having rid himself of his load, turned, hesitated, and then said gruffly:

"We keep sentinel. It is my duty hour." And was gone.

"There have been others---those you must watch for?" Lethe asked.

"None since the corning of Truas and Tristy." The oldest girl nodded toward the twins. “They came over mountain three tens ago. But the demons had wrought evil down by the sea---earlier. There was a village there once.”

"Yes," Lethe agreed, “there was once a village.”

"It had been taken long ago," the boy who had borne the club volunteered. "We---we are all from over mountain, Lusta and I---I'm Tyffan, Hilder's son, of Fourth Bend. We were in the fields with Uncle Stansals. He bid us into th' wood when there was smoke from th' village over hill. But”--- the boy’s fists clenched and there was a grim set to his young jaw--- “he did not come back. We had heard of th' demons an' what they did to villages, still we waited in hiding. No one came,"

The girl Lusta looked into the heart of the now bravely burning fire. "We wanted to go back---but we saw th' demons riding an' we knew we could never make it."

Truas, tending the fire, looked over his shoulder. "We're shepherds and were out after a stray. They saw us but we knew th' rock trails better. At least those devils cannot fly!"

"Hurten was shield-bearer for Lord Vergan," the oldest girl spoke up. "He was hit on the head and left for dead in the pass battle. I am Marsila and he” ---she pointed to the younger boy who had been on the wall---"is my brother, Orffa. Our father was marshal of the Outermost Tower. We were hunting when they came and so were Cut off---"

"How carne you together?" Lethe asked.

Marsila glanced about as if for the first time she herself had faced that question.

"Lady, we met by chance. Alana and Robar, they fled to Bors Wood and there met with Lusta and Tyffan. And Orffa and I, we found Hurten and stayed with him until his head was healed, then we, too, took the wood road. There was, we hoped, a chance that Skylan or Varon might have held---only, when we met the others, Alana said the demons had swept between to cut us off.”

"You decided then to come over mountain? Why?" Lethe must know---already she sought the beginning of the pattern she had sensed. There was one or she, the weaver, would not have been summoned.

It was Lusta who answered, in a low voice, her head down as if she must confess some fault. “The dreams, lady. Always the same dream an' each time I saw clearer."

"Lusta's gran was Wise," Tyffan broke in. "All of Fourth Bend thought she had part of the gift, too. Lusta dreamed us here."

Marsila smiled and put her arm around the younger girl's shoulders. "Not many have the Wise gifts now, but we had records of such at the Tower and---well---we had no other place to go, so why not trust a dream?"

Her face became bleak again. "At least the demons did not try the mountains then. When we found this place we knew that fortune favored us a little. There is farm stock running wild in the valley, patches of grain we are harvesting, and fruit. Also---this place, it seemed somehow as if we were meant to shelter here."

"Dreams led!" Lethe moved to Lusta and, as she had with Alana, touched the girl's head with her staff. There was a spark of blue. Lethe smiled.

"Dreamer, you have wrought well. Good will follow in a way now past your understanding."

Then she drew back to survey them all, her gaze resting for a long moment on each face, so this was indeed the beginning.

“Truly," she spoke, "this is the place for such as you."

These were from very different beddings, these seedlings, yet their roots were the same. That had been clear to her from their first sighting. Their hair, tangled, unkempt, was of the same pale silver blond, their eyes shared the same clear sword-blade grey. Yes, the old stock had survived after all, though the seed might have been wide flung.

Lethe shifted the bag she had carried from her shoulder to the top of the table. She loosed the string and reached within, drawing forth a packet of dried meat, another of herbs.

There was already something steaming in the great pot; she was certain that they had not lost the chance for a day's hunting. Now she shook forth her own offerings and added them to that. They watched her closely.

"Traveler's fare, but it may add to your store as is the custom," she told them.

Marsila had watched her very closely. Now, in spite of the fact that she wore breeches patched with small skins, she made the curtsy of a daughter of a House in formal acknowledgment.

"If this be your kin, hold our thanks for shelter." Still there was a measure of questioning in her eyes.

However, it was Alana who spoke, and she did so almost with accusation. “You are one of Them so this is your place."

"What do you know of Them, child?" Lethe had shrugged off her cloak. Her breeches and jerkin were of a dull green not unlike the walls about her.

"They had strange powers," Alana answered. She reached out and drew Robar to her. "Powers which gave them rule. None could stand against them---like the demons!"

Lethe had taken a ladle from a hook in the hearth wall. Now she looked directly at the small girl. "Powers to take rule like the demons---that what they say of us now?"

For a long moment Alana was silent and then she flushed. “They---They did not hunt people---They did not kill---"

"They were guardians!" Marsila broke in. “When They were in the land there could be no death there."

"Why did They go?" one of the twins sat back on his heels.

"When They had strong keeps like this, if They ruled th' land, what did They do?"

Lethe stirred the pot. She did not look around.

"The land is old, many have been rooted here. When years pass another blood comes to masterage."

For the first time Orffa spoke: “So this is the time for demons to rule, is that what you tell us?" There was a fierce challenge in his voice and he was scowling.

"Demons?" Lethe looked to the fire and the steaming pot. "Yes, to this land at this hour, they are demons."

Marsila moved closer. "How else can we see them? Tell me that, once guardian!"

Lethe sighed. "No way else." She turned to face the children, Children? Save for Robar, there was little childlike in those faces ringing her in. They had seen much, and none of it good. But that was the working of the Way, the spinning of the weaver's threads. Standing in shadow behind each was the faint promise of what might be.

"Why have you come? Will others follow you?" demanded Orffa.

"I have come because I was summoned. I alone." She gave them the truth. "The kinblood have passed to another place, only it would seem that I am tied to this day."

“This is magic.” Tyffan pointed to her staff where she had laid it across the table. "But you're one against many. Those raiders hold th' land from Far River to th' Sea, from Smore Mount Mouth to Deep Yen.”

Lethe looked directly at him, His mop of hair reached barely above her shoulder, but his sturdy legs were planted a little apart, and he stood with his fist-curled hands on his hips as if in defiance.

"You speak as one who knows," she commented.

To her mild surprise he grinned. "Not claimin' magic, mistress, that. You find us here now, that's not sayin' as how we is always here. We has our ways o' learnin'. What chances over mountain---and it ain't by dreams.”

Lethe pursed her lips. Inking at him she could believe in what he hinted. This one had stated that he was land-born, land-trained; and the young learned swiftly when there was need.

“So you have used your eyes and ears to good purpose. He nodded briskly. “Well enough. And what have you learned with your non-magic?"

Orffa pushed past the younger boy. "Enough," he snapped.

"And the demons have not disturbed you here?" she asked.

"There was a scouting company," Marsila answered. "They followed the sea road inward but there carne a sudden rockfall which closed that. At night they camped near that . . .”

Tyffan grinned widely and the twins echoed his expression.

'They didn't like what they heard nor saw. We didn't either, but then we guessed as how it weren't meant for th' likes of us. They ran---an' some o' them went into river. Hurten, he brought down one with an arrow---he’s a champion shot---an' we bashed a couple with rocks. Wanted to get their weapons but river took 'em an' we didn't dare go after 'em. They ain't been this way since."

“It wasn't us, not all of it," Marsila said slowly. "There was something there---we felt it but it did not try to get us---only them."

Lusta held to the other girl's arm. "The rocks made shadow things," she said.

“So the old guards hold somewhat," Lethe commented. "But those were never meant to stand against any who meant no harm. This”---she gestured with her hand---“was once a place of peace under the sign of Earth and Air, Flame and Water.”

"Now,” she pointed to the pot, "shall we eat? Bodies need food, even as minds need knowledge."

But her thoughts were caught in another pattern. Here was a mixture which only danger could have, and had, cemented---delvers, shepherds, soldier and lordly blood all come by chance together and seemingly already united. Chance? No, she thought she dared already believe not. They brought bowls and marshaled in line. Some had battered metal, time-darkened, which they must have found here; there were cups shaped of bark pinned together with pegs. Lethe tendered the ladle to Marsila and watched the girl dip careful portions to each. One over she set aside and Lethe took it up.

"For your sentinel? Let this be my service."

Before any protested she headed out of the great kitchen. The dark had deepened despite the globe light, but she walked with the sure step of one who well knew the way, just as, once without, she climbed easily to the wall top.

"No need for that.” She had heard rather than seen the draw of a belt knife, could picture well the spare young body half acrouch. “Your supper, sentinel, also your relief.”

Shadow moved out of shadows. In her left hand the staff diffused a pale radiance. Though Hurten reached for the bowl, the dagger was still drawn. However, Lethe took no notice of his wariness. Instead she had swept the staff along the outer edge of the parapet that sheltered them a little from the incoming sea wind.

"So are guards set, Hurten. I promise you that there need be no watch on duty this night. And there is much we all have to talk of . . .”

She could sense the edge of the resentment that was rightfully his. What leadership this group had known in the arts of war must have come from him.

"Shield Chief," deliberately Lethe used the old tongue, "there is a time for the blooding of blades and a time for planning, that those blades may be better sharpened for the blooding."

"By oak, by Stream, by Storm, by Fire---" The words came in the old tongue---

Lethe nodded, though he might not be able to see that gesture of approval in the gloom.

"By Sword and Staff, by Horn, by Crown." The old words came so easily in this place, though it was another time when they were common here. “So warrior, you have at least trod a stride or two down that path?"

"My lord was of the House of Uye. When we were given our swords as men he held by the old oaths."

Swords as men! she thought. These must be dire days when boys were counted men. But only dire days have drawn her here.

"Then you know that this is a place of peace.”

She heard the faint snick of the dagger being sent once more into sheath.

"Lady, in this land there is no longer any place of peace." His words were stark and harsh.

"To that we shall take council. Come---"

Hurten hesitated, still unwilling to admit that the watch he had taken on himself might no longer be necessary, but she had already started back as if she thought there could be no questioning, and he followed.

They found the rest about the fire. Orffa and Marsila both looked up in question as Hurten came in, but Lethe was quick to explain:

"There is a guard, and one which will keep the watch well. For now there is that which we must discuss among ourselves. Deliberately she chose her words to ally herself at once with these chosen for a purpose she could not question.

"Time may change but not the seasons." Lethe had waited until they had cleaned their bowls. "The sea winds herald ill coming. There was once some command over wind and weather in this place, but that was long ago. We shall need that for day and night” ---she pointed to the fire---“and food---"

"We have been gathering," Marsila answered sharply as if some action of hers had been called into question. 'We have a storeroom."

Lethe nodded. “That I do not question, Save that if the dire storms hit, as well they may, there shall be needed every scrap of food, every stick of wood. Herb-craft also, for there are the illnesses which come with weather changes, and some of those are severe."

There was movement at the other side of the table. Alana carried a nearly asleep Robar to one of the fireside pallets.

Hurten leaned forward.

"What are we to you?" His voice was a little hoarse. "We are not of your breed. No." He glanced briefly at the others. "Nor are we even of one House or blood ties ourselves, We make no claim of vassalage rights---"

"Why did you come here?" Marsila planted one elbow on the table and rested her chin upon her hand. 'There has been no tale of your kind among us since the High Queen Fothuna died, leaving no daughter for the rule, and all the land fell apart, with quarrels between lordlings and War Ladies. And that was a legend length of years ago. We have none of the old power---

"Lusta, yes. Twice she dreamed us out of fell dangers---but our race was and is wise in our own way only. Thus we ask, why do you come to speak as a chatelaine here?"

"And I ask again, what do you want with us?" Hurten repeated.

He was frowning, and that frown was echoed by a stronger scowl drawing together Orffa's straight brows. The impish humor that had looked ever ready to curve Tyffan's lips was gone, and the twins were blank-faced.

Lusta's tongue showed a pink tip between her lips but she did not speak, and Alana's hands clasped together tightly on the table top before her.

"You, in a manner, called me. No”---Lethe shook her head, aware of the denial already on Hurten's lips---“I do not say that you knew of me. But in those days of far legend Marsila has mentioned there were gaes laid, and this was mine: that I was tied to Kar-of-the-River---this keep in which we shelter. And so I fulfill now that set upon me. I did not know until I came hither what I would find.

"As to what you mean to me---that we both must learn. For I must in right tell you this, that you are bound even as I---“

Hurten's hand balled into a fist. He moved as if to stand. He was of no temper to play with words, as Lethe saw, yet what more could she tell him yet?

It was Orffa who got to his feet and moved behind the older boy, as a liege man would back-cover his lord. But of him Hurten took no notice as he said:

"Lady, we are not those for your binding."

Lethe sighed. Patience, ever patience. A weaver must be sure that no knotting despoiled her threads. It was Marsila who put an end to it.

"The hour grows late." She had pulled Alana closer beside her, and the child leaned heavily against her shoulder. "With the morrow there will be time enough for questions."

It seemed that even Hurten was willing to surrender to that. So the fire was set for long burning and they took their places on the pallets within its warmth, Lethe lying down upon a cushion of her cloak--- though she did not sleep. For her kind needed little of such rest. Instead, behind closed eyelids, she rebuilt what now closed her in as she had seen it last in other days. Out of the past she summoned others who moved as shades where they had once been true life.

A sound broke through her half-dream. She opened her eyes. One of those on the pallets had sat up, aside a covering of skins. The fire flickered to show a face---

Lusta, the dreamer!

Lethe's keen sight was not deadened by the gloom. The girl's eyes were closed. Nor did she open them as her head swung around as if in answer to some summons. On hands and knees, eyes still shut, she crawled away from the hearth into inner darkness, and then got to her feet. Lethe allowed her a small start and followed after.

Down the hall into the great presence chamber. The globe light was gone, it was totally dark here, yet Lusta went with the confidence of one who saw perfectly. Lethe followed. To break the girl's trance---no---that was a dangerous folly. She must know what drove Lusta into the night.

They came forth from the hall into the open of the courtyard. Up the stairs Lusta went without a stumble. A moon shone warily between moving clouds, and to Lethe this was light enough. Lusta had sought out the very perch where Hurten had earlier made his sentry post.

She turned slowly, facing outward, and then her hand went out to the parapet and her fingers tapped along it. Sparks flew as if she used a wand of iron instead of her own flesh.

Lethe's head went back, Her nostrils flared as if to catch some faint scent. She was already up the stairs; now she moved forward, and, standing behind Lusta, put out her own two hands, touching fingers lightly to both the girl's temples.

The woman's lips flattened into something closer than a snarl. This---but she had not thought that the new invaders were so knowledgeable. Or were they only symptoms of an older and fouler plague?

She applied pressure, flesh to flesh, and forced will upon dream. Lusta's own hands paused in their tapping. 'Then she cried out sharply and crumpled as if all life had been withdrawn in a matter of a breath or two.

Lethe did not kneel at once beside her; rather she now turned all attention to the danger at hand. Where Lusta had wrought a breaking spell, she relaid the guard, this time reinforcing it with will enough to leave her feeling nearly as drained as the unconscious girl at her feet.

It was not well---what she had done would alert that other power that had already made this first move. Yet Lusta taken over, with a gift she had not been trained to protect, was a key which must not be used.

Lethe crouched down to gather the girl into her arms, pulling her cloak about the both of them, Lusta's was as chill as if she had been brought out of a snowbank, but both of her hands, which Lethe took into one of hers, were warm, near fire-hot, That which the girl had not finished projecting into the break spell was turned back upon her, eating

in. She moaned and twisted in the woman's hold.

"Lusta!" There came a call from below, then the scrape of boots on stone.

Tyffan came in a scrambling run. "Lusta!" He went down on his knees beside the two of them. “What---“

"She is safe---for now.” Under Lethe's touch the fire had cooled from the girl's hands. "Tyffan, you say she dreamed you here?"

'What is wrong with her?" He paid no attention to that question.

"She has been possessed." Lethe gave him the truth. "Perhaps even her dreaming you here was by another's purpose. This night that which held her in bond used her to attack the guards."

Tyffan stared at the woman. "But Lusta would not---"

' 'No!" Lethe assured him quickly. “She would not have brought harm to you willingly. But she was not taught to guard her gift, and that laid her open to---“

“The demons!" But how---“

'We do not know by whom or why she was sent to do this," Lethe said quickly. "But she has overused her strength, and we must get her into warmth now."

Hurten and Orffa met them at the door of the presence chamber, and Tyffan gave them a confused answer as to what had happened as hurried the girl, who was on her feet but barely so, into the warmth of the kitchen place.

She oversaw the brewing up of an herbal potion and stood over Lusta until the girl drank it to the dregs. Lusta seemed but half awake, dazed, mumbling, and unaware of where she was or what had happened. Lethe saw her back to the pallet and then faced the others.

"You asked me earlier what I wanted of you," she said directly. “That I do not yet fully know. But it may also be that another power brought you here and is prepared to make use of you." And she explained what Lusta had been led to do.

"Lusta is not a demon!" Tyffan near shouted.

It was Marsila who answered him. “She is Wise. That is a power. Lusta would never use it for any but good, In truth”---now she spoke to Lethe ---“she never used it by her will; the dreams came to her without her seeking or bidding."

“'We speak of power as a gift," Lethe said. "It may also be a burden, even a curse, if it is not used with control. I do not think that Lusta was given any aid in learning what she could do---"

Tyffan stirred. "She---she didn't know as how it meant anything." He looked toward where the girl lay. "Her mam, she died when Lusta was just a mite. M' mam, she was closest kin an' took her. But we had no Wise for a long time. T’wasn't 'til after th' demons came that she dreamed---or at least told her dreams. But she's no demon---ask Hurten---ask Truas and Tristy. She dreamed us together!"

"The demons,” Lethe returned. "Have you heard that they have some form of the Wisdom among them?"

The children looked to one another and then Marsila shook her head.

"They came like---like storm clouds---and there was no standing against them. There were so many and they seemed to appear without any warning. But my father said we fared so badly in the field against them because the lords and War Ladies had been cut adrift from any one leader. Each fought for their own holds, and one by one those Holds fell. There was no High Queen. It was almost as if we were all blinded---“

Hurten nodded. "My lord---he tried to send for help to the Hold of Iskar, and the lord there told him no because he feared those of Eldan more than the demons. He told the messenger that the rumors of demons were put about to frighten timid Hold-keepers. That was before Iskar was taken in two days and left but bloodied stone, There, it is true"--- he spoke thoughtfully now, almost as if he were examining memory and seeing a new pattern in it---“that the Holders did not come together. And what they gave as reasons were mainly wariness of their own neighbors. Was that---could that have been some power of the demons?"

His hand had gone once more to the hilt of his dagger and he stared at Lethe as if he would have the truth even at a point of steel.

"It could be so."

It was Alana who came a step or so closer and looked up into Lethe's face.

"Lady, why would the demons want us who are here in this place--- unless to kill us”---she hesitated a second and the old fear came flooding back into her firelit eyes---“they did all the others? Lusta dreamed us here---but there were no demons waiting.”

"This was waiting, and perhaps your entrance here would open doors for them or something else." Lethe was searching---her senses weighing first the children and then the very walls about them. No, there had been no tampering save that she had caught this night. There was no taint of dark in this company.

"What lies here then?" flared Hurten. "The demons came upon us from the north; they are not of our kind. Perhaps"---his eyes narrowed---"they are of yours---lady." And there was little goodwill in the title he gave her.

"Before your demons," she answered him, "there were other powers abroad. Some were always of the Dark. Open your mind, youth: is this such a place as welcomes the Dire Shadows?"

For a moment there was a silence, Hurten's frown did not fade. Then tentatively his right hand arose between them and the fingers moved in a gesture that brought a sigh of relief from Lethe.

"Bite of iron, warrior." She held out her own hand. He hesitated, then drew his dagger. She deliberately touched the end of the blade, withstanding a stab of flame pain that was true fire. When she took her hand away and turned it over, she held it well into the light.

There was an angry red blotch on her pale skin. She endured the pain for a space, that they might see, and then willed healing into the skin.

"Cold iron.” Hurten looked down at his own weapon as if it possessed a potential unknown to him.

'The demons," Orffa broke in, "can die but from edge and point. Only the First Ones---" He drew a deep breath.

"Only those of the Right-Hand path," Marsila interrupted her brother, "cannot hold iron."

"And our wards still held here," Lethe pointed out, "Still there must be that which would put an end to weaving by destroying loom and weaver.”

"You speak of weaving," Marsila said then. "You are the weaver?"

"So it has been set upon me."

"It remains." Hurten turned to the earlier problem. "Lusta led us here, by whose will?"

"Who can tell that?" Lethe spoke wearily, for again the truth burdened her down.

'Will---will she be possessed again?" Marsila approached Lusta with caution. The younger girl appeared deep in sleep, unaware of all about her now.

"l have set guards," Lethe answered. "For now those will hold."

None of them questioned that---as if they avoided voicing doubts. Hurten settled by the fire, but not to sleep. Instead he brought from a belt pouch a whetstone, and with this he set about giving edge to his dagger, working as one who must occupy himself with even so small a preparation against trouble to come. Marsila dragged her pallet up beside Lusta's, just as Tyffan barricaded the girl on the other side.

Hurten's belt with its empty scabbard---without a sword---

Without a sword, that symbol of manhood for his race. Lethe once more closed her eyes, but her thoughts were awake. A sword---she resisted, having the feeling that she was being pushed too swiftly into decisions. It was not for her to deal with weapons as this land now knew them, but neither could she deny to others the safety a blade offer. However, this could wait until tomorrow. Hurten had stopped the push of the whetstone, returned it to his pouch, was stretching out to sleep.

Lethe lengthened the narrowest edge of thought as a field commander would dispatch a trained scout. The guards were firm, nothing tried them. Lusta? The girl was so deep in slumber that no invader could reach her. Safe? Were any of them safe?

Lusta had offered a gate to some old power---what of the other children? Lethe shrank from what she must do---this was something that could only be justified by dire danger. Did they face that?

She made her decision and began the search. Alana, one arm thrown about her little brother in constant protection---nothing there.

The shepherd twins? A hazy dream picture, partly shared, of a fair morning in home heights. Tyffan---dark shadows acreep---the beginning of a nightmare in which he struggled to reach a farmhouse where Lusta awaited him. That she could banish, and she did.

Marsila---fall woodlands in brilliant color, a sun-warmed morning---rightness and loving memory. Her brother---deep sleep as untroubled as Lusta's. Hurten---the sentry on the wall, a pressing need to hold off some threat that had not yet shown itself---a need the greater because he had no weapon, She had been right---this one needed the talisman of a blade.

Lethe searched memory. She had read them and there was no taint here. So assured, she could await the coming day.

They broke their morning fast with a rough mush of wild grain only made palatable by a handful of dried berries. Lethe waited until they were done before she spoke.

"You have two bows, two daggers among you---that is not enough."

Hurten laughed angrily. “The truth, Lady. But here there is no forge, nor are any of us smiths. Is there an enemy we can hope to plunder?"

"Come---"

Lethe led them back to the presence chamber, all, even Robar, trailing her. She came to face the wall behind the dais. There hung one of the time-ravished lengths of weaving. This was no tapestry like the others, rather the remains of what might once have been a banner.

So hard had time treated what lay here! However, she was not saddened, rather stirred by the need to be about her task. The chairs that had once stood against the wall were debris. But the long table there was intact, save it was covered with dust and splinters of wood.

She swept out with her staff, and the litter was lifted and blown away by a strong puff of breeze. Lethe pointed now to the frail banner.

With the staff she drew a careful outline around what hung there while she hummed---a faint drone of sound, like the sigh of wind in a wood. On the wall the banner moved. Dust motes shifted down, but none of the frail fabric parted. As a single piece it was loosed while her staff moved back and forth as might that of a shepherd guiding a flock around some danger. Down came the length of ancient weaving, to lie full-length on the table.

"Do not touch it!" she ordered. "That time is not yet. We have other needs."

Once more her staff moved, now pointing directly to the wall the banner had curtained. She spoke aloud in command, words that had not been uttered since the days of deep legend.

Cracks appeared between stones, lines formed a doorway. That opened.

“Come!" Lethe waved them on.

The staff itself gave forth the light here, bringing answering gleams from racks, from shelves for storage. Here were weapons. She heard a cry from Hurten as he pushed forward, his hand out to the hilt of a sword. He stood looking down at it in joyful wonder. The others ventured farther in, eyeing what was there as if they did not quite dare touch. Then Orffa took up a sword, and Tyffan, after glancing to Lethe as if she might forbid it even now, closed hand upon the haft of a double-bladed axe.

A moment later Hurten turned accusingly to the woman. "What folly is this? No true steel---" He had been running his hand along the blade of his choice.

She laughed. "Cold iron is not to be found here, young warrior. These are forged of battle silver, but none the less sharp and strong.

For a moment it seemed as if he might dispute that, then he nodded.

"To each people their own secrets. This balances well at least." He swung it in a practice thrust.

“No—no---Robar!”

Alana was in a tug of war with her brother. Face red with rising anger, he was struggling to get full hold on a dagger near long enough to be deemed a short sword.

"Want---want---now! Robar wants---!"

Alana seemed unable to break his grip. Truas caught the little boy by the shoulders from behind.

"Here now, young'un, that's naught to play with. Give it to Alana an'---" He had turned his head to view the racks of weapons but was plainly baffled as to what might be offered as a counter to Robar's first choice.

' 'Want!" Robar howled and then aimed a kick at his sister that struck home before Truas could pull him out of' reach.

"Robar---no---!" There was an expression of fear on Alana's face.

"Give it to Alana, please!"

As the boy fought and wriggled to free himself, Alana pried his fingers loose one by one. His screaming was enough to bring all the others to the battle. Once his sister had forced one hand open, Robar swung that up and drew his nails down her cheek. She cried out and jerked back, her eyes wide, staring at her brother as if she had never seen him before.

Marsila pushed her aside, but it was Hurten who took command:

"Give him to me!" And when Truas had surrendered the still wildly fighting boy into his hold he added, “Get that thing away from him!"

In spite of having to ward off kicks, which, to Lethe, appeared too well aimed to be allied with blind rage, Truas was able to capture the dagger. Then Hurten carried the still struggling child out of the room.

Alana's whole body was shaking. Tears diluted the blood from the scratches on her cheeks.

"He---he never did that before. Oh, Robar!" She pushed aside Marsila and ran after Hurten and her brother.

There was a subdued quiet. Lethe stooped to pick up the disputed weapon. To both her eyes and her inner touch it was no more than it appeared to be. For a moment a wisp of thought had troubled her. But the scene could have risen simply from the fact that an over-guarded and indulged child---for Alana's care was easy to see---had wanted a choice like the other boys. He was passing out of babyhood and perhaps had been unconsciously resentful of Alana's protectiveness for some time.

The others made their choices quickly. Marsila chose four bows and matching quivers of silver-tipped arrows, gathering them into an unwieldy bundle. Lusta and the others selected daggers, testing the points on fingertips. But for major weapons the twins wanted short-shafted javelins, taking a trio of these apiece. Tyffan held to the axe, Orffa the sword with a belt and sheath to go with it.

Lethe was interested in their choices. Each must have chosen those arms with which they felt the most comfortable. She replaced the dagger Robar had clung to in the rack, and followed the company out. Behind her the door closed and once more disappeared.

Marsila laid the bows down on the table, taking care not to disturb the banner. She motioned to Lusta and Orffa, and they each chose one. Then she selected hers, leaving the other.

“Hurten’s”---she nodded to that---“a far better one than he has, and one to serve him well."

Alana sat by the pallet when they reentered the kitchen. Robar lay there curled in himself sniffling. As the others drew near his sister pulled at his shoulder.

"Robar?" Her voice both admonished and encouraged.

He sat up. The anger had gone out of his eyes. Instead tears marked his cheeks.

"Sorry---Robar's sorry." His voice was hardly above a whisper.

Alana smiled. "It's true, he is sorry."

Marsila went closer, “Very well, Robar. But being sorry does not take away the scratches on your sister's cheek, now does it?"

He smeared both hands across his face. "Robar's sorry," he repeated woefully, Alana caught him in a tight hug.

"Of course, Alana knows, Robar's really sorry."

Tyffan, fingering the new axe, had seemed to pay little attention. Now he said:

“Tis a fair day out. Maybe there will be a beast in the grasslands---easy to be downed with new bows."

"Of course!" Hurten appeared with the bow Marsila had left for him. “Get us perhaps that yearling bull calf we saw two days ago.”

Lethe watched them scatter to what must have been the occupations they had settled to since they had come to the keep. In the day there was no fear of the outlands.

Even Robar shared in the gathering of supplies, disputing with a number of angry squirrels for the harvest of fallen nuts, while his sister and Tristy beat the tree branches to bring more down.

Lusta was using her new dagger to cut raged stands of wild grain still slippery from yesterday's storm. Her harvesting sent grain-eating birds flying, and she turned to her bow. Though it was apparent she was no well-trained archer, she did not always miss.

Lethe left the scene of labor and followed the river, pausing now and then to stand, staff in hand, spying out toward the hills in her own fashion. But if Lusta had nearly opened a door to something of the Dark last night, it was not to be sensed now.

Though her warning sense kept guard, her main thoughts turned to what had drawn her here and why. These children seedlings, threads---hers would be the planting, the weaving. She tightened hold on her staff. After all the years to have once more a purpose!

Lethe returned to the keep at midday to stand again in the presence chamber, looking down at the ghostly banner. Her fingers moved as they might, without direction but from long habit. Slowly she turned to survey the huge chamber. Where there was desolation---yes, there would be life again.

In the kitchen was truly the bustle of life. Hurten had indeed brought down the bull calf and roughly butchered it. And now it lay bundled in its own spotted hide; containers of bark, even large leaves pinned together with thorns, were full of the last of the berries, nuts, edible roots, all of which Lusta was sorting with the help of Alana; while Marsila had brought in a string of ducks.

Hurten appeared again with the twins, and this time they had not plundered the moldering furniture in the other rooms, but had good loads of wood, storm gleanings---though these must be set to dry.

They shared the work as if they had done this many times before, and Lethe nodded. Already these were bonded after their own fashion; her task would be the lighter.

Through her self-congratulation broke a cry of fear. Alana had pulled away from the table.

"Robar---where is Robar? Tyffan, did he follow you again? Where is he?”

"Never saw him." There was an odd note in the older boy's voice. "What do you mean, followed me?" He was so quickly angry, as if he had been accused of some wrongdoing.

Lethe tensed. Now there was something awakening here, hostile to the accord that had lulled her.

Orffa was also showing signs of anger. "Little pest, always creeping around where he shouldn't be," he muttered.

Alana was confronting Tyffan. There was fear but anger also in the words she flung at him.

"When you passed us you said you were going to the pond. You know how he loves to go there."

Tyffan shook his head. "He wasn't with me, I tell you."

She turned then on Orffa. "You were hunting up on the hill, you must have seen him."

“I never saw the brat. He's always in some trouble or other. Best tie him to you and be done with it, trader trash!"

"Mind your mouth!" Marsila snapped at her brother. "If Robar did go to the pool---“

Alana let out a keening cry and darted for the doorway, Marsila but a step or so behind her. A crash sounded from the table: Lusta had dropped one of the metal bowls. Hurten caught Orffa by the shoulder and jerked him around to face him.

"That pool is deep, Orffa. Also, there are no 'trader trash' here. Keep that tongue of yours clean!"

Orffa's face was scarlet as he jerked free from the other's grip.

"I never saw the brat!"

Lethe shivered. She had been a sentry---surely she would have sensed evil in the valley this morning if it had lain in waiting there. The contentment that had been here only moments earlier was shattered as if she had willed it away herself.

Lusta? Her gift; that was understandable. Robar? Lethe had sensed no power in him, but he was so young a child that at his age he would have very few natural defenses. Robar---!

Not the pool, no. What was wanted for Robar was not danger for him, but through him. And what was wanted must lie within these walls.

"Fool!" Hurten snarled at Orffa. The younger boy's hand flew to his sword hilt. Now the twins moved in and Tyffan was rounding the table to join them. Lusta stood with her hands pressed to her whitened cheeks.

"Keep your tongue to yourself!" Orffa cried. "Do not try to play the high lord with me! I do not know where the brat went---"

"He came here," Truas said. “Saw him on the bridge.”

Orffa showed teeth. “Why didn't you speak up before, thickhead---or were you so gagged with the dirty wool you couldn't?"

"Here now," Tristy answered before his brother. He still held the bloody knife he had been using on Hurten's kill. "What's gotten into you, Orffa?"

“Orffa?" He made a near threat of his own name. 'Who are you to name me so familiarly, beast-keeper? I am of the blood of Ruran who was lord---"

'Stop!" Lethe's staff was between the boys. Her eyes had narrowed as she looked from one furious scowl to another. "You saw Robar come here? Then let us find him." Either the tone of her voice or some effect of the staff brought them together again---temporarily.

' 'We'll search---" Hurten agreed.

"Perhaps there is no need to go far." Lethe beckoned to Lusta and asked, “Which of those boxes of nuts there did Robar fill?"

Lusta shivered, and her hands whipped behind her back. "No! No!" She turned her head from side to side, like a small trapped animal gnawed by fear.

"Yes!" There was no escaping that order.

Lusta's right arm moved outward, her fingers hooked like claws. She was staring down at the array of the morning's harvest with fear-rounded eyes. Her hand swung, steadied over one of those containers.

Instantly Lethe raised the staff and touched the crude basket.

She had their full attention now, their quarreling forgotten. Her grip on the staff was loose enough to allow it play, swing of its own accord. She followed that direction, the others close behind her.

Back into the presence chamber---to the wall of the hidden room. She had been a fool to underestimate this other power. That early scene with Robar in there---why had she been so blind?

She strove within her to trace, to know---

"There must be all of you here. Find Marsila---Alana---"

Lethe did not look to see if she had been obeyed, but she heard the shuffle of badly worn boots across the hall.

"Lady." Lusta had crept to her side. “Lady I am afraid---I cannot---I do not know what you would have me do."

"Nor do I know yet what has to be done, child. As for can and cannot, Lusta, that will wait upon what we learn."

She fought within her to set aside all the lives about her, to think only in terms of her weapon---no blade nor axe, spear nor bow, only what was her own. As she wove life, so now she must weave another sort of web, one to be both defense and trap.

"Robar! Please.” There was a tug at her arm. "Is Robar truly here?" Lethe looked around quickly---not only Alana was here, but all the rest.

She began a chant, the words issuing stiffly from her lips as if it were so long since they had been used that they had grown as rusty as untended armor. Once more the concealed door opened.

Around them the globe lights dimmed as if their radiance was being sucked out of them.

Lethe threw out her arm to catch Alana, who would have darted before her.

"Robar!" his sister screamed, and then her voice was muffled, for which Lethe was briefly grateful.

The light of the staff flared. In the armory a shadow sprang forth from shadows---and the light caught on a bared blade.

Lethe's weapon swung down between her body and that intended blow. Robar crouched. His face was not that of a child. That which had entered him had molded his features, was blazing from his eyes.

The staff swung, pointed. Sparks formed into a tongue of light, but that was fended, curled back, before it touched the child.

“Join!" Lethe's other hand moved as her voice rose above the insane shrieks from the small figure before her. Spittle flecked from his lips. Dread intelligence stared grimly and grotesquely from his eyes.

"Join!" Her free hand was gripped, she felt the surge of energy, then came a second and a third---that which had first brought them together was still in force.

The staff warmed. The thread of solid light from it was still held away from Robar, but the space was less and less.

"You are Robar!" Lethe called upon the power that lay in names. "You are one with this company. You are Robar!"

Small lips twisted into a sneer.

"Fratch!"

Lethe was prepared. That challenger name did not surprise her. As there were the weavers among the kin, so there had been destroyers. But time was long, and that which destroyed never grew without feeding. Had it been the invaders who had fed this one awake again?

"You are Robar!"

She sought the Touch, to seek out, to shift one personality from another. The light spear was now less than a finger-width from the grimacing child.

"Robar!" That was meant as a call, a summoning. At the same time she drew deeper on the energy fed her by the others.

The light touched the child's forehead. His features writhed and he howled, a cry no human could have uttered. Then---it was as if something that had been confined in too small a prisoning burst forth.

Robar fell like a crumpled twist of harvest grain. Above his body wavered a mist into which bored the spear of light. Then the mist spiraled downward upon itself until it was but a grey blot which the blue bolt licked into nothingness.

"Robar!" Alana threw herself at her brother, pulling him close, twisting her own body about him as if to wall him from all harm.

"What---what happened, lady?" Tyffan asked hoarsely.

“That was a shadow, of something which should have died long ago.” Lethe tried to take a step and tottered.

Strong young arms closed about her as Hurten and Marsila moved in. "A shadow of a will. First it tried to fasten onto Lusta, for her gift offered it power. Then it turned to Robar because he was too young to have those safeguards which come through living, Fratch---Styreon who was”---she addressed the empty air---“you were ever greedy for that which was not yours---nor shall it ever be!"

They went out of the armory, Orffa carrying Robar, who lay limp in his arms, Alana seemingly content to have it so. Marsila and Hurten kept their hold on Lethe, the end of her staff dragging on the floor, though she still kept it within her grasp.

Here was the table on which lay the banner. What was to be done was clear now, and the sooner done the better. Lethe spoke to Lusta:

"This is a beginning. Sister, take your dagger, that which is of the great forging, and not made of fatal iron, and cut from the head of each of these comrade-kin of yours a lock.”

They asked no questions, and submitted to Lusta's knife. For the first time set aside her staff. From her belt purse she brought forth a large needle, which glistened gold in the light. This she threaded with a strand of hair and set about weaving it into the webbing as one would darn a very old and precious thing. So she did again and again as they watched. And with each new strand she repeated aloud the name of him or her to which it had belonged, forming so a chant.

Thus Lethe wrought in moments lifted out of time, for none spoke nor moved, only watched. When she was done they looked upon a length of silver-gold on which faint patterns formed, changed, reformed, growing ever the stronger.

Lethe withdrew her needle. “One is combined of many, even as you united in your flight out of death, as you me of your strength to free Robar---you are indeed one.

"But from that one weaving there will come much which is to be welcomed---and time will welcome it and you.”

It is told that in the fell days when the Ka-sati had laid totally waste the land and those of the barbarian blood would raise a temple to the Eternal Darkness, there came a company out of the northern hills, riding under a banner bearing nine stripes of gold. Those who bore it were of the blood of legends and what they wrought was to the glory of earth and sky, flood and flame---the darkness being utterly blinded by their light.