Grimoire X

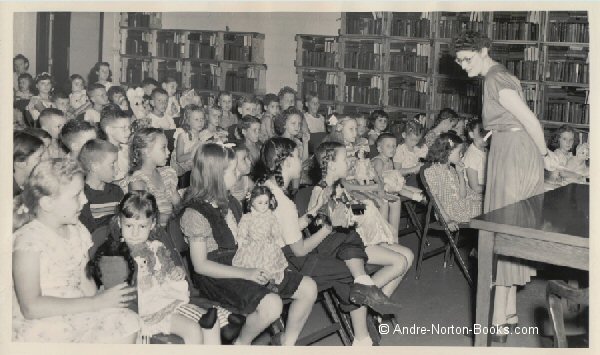

Andre the Librarian hosting "Story Time" at the Cleveland Public Library ~ 1948

"Come on In! . . .Take a Seat! . . . and Settle Down! . . ."

As the Ghost of Andre shares with you a tale by one of the leading story tellers of the past century.

Once a Month (on the 1st) We are going to post an original story by Andre Norton

During the showcase period you will be able to read it here free of charge.

Many were only published once.

So, it's a sure thing that there's going to be a few you have never heard of.

The order will be rather random in hopes you return often.

Happy Reading!

Swamp Dweller

by Andre Norton

I am Quintka blood, no matter my mother. Shame-shorn of skull, snow-pale of skin, her body crisscrossed by lash scarring, her leg torn by hound's teeth, lying in a ditch, she bore me, to hide me in leaves before death came. The Calling was mine from the first breath I drew, as it is with all the Kin, and Lari, free ranging that day, heard, pawing me free, giving me the breast with her own current nurseling, before loping back to Garner himself to show her new cubling.

Quintka I plainly was by my wide yellow eyes and silver hair. Though my mother was of no race known to Garner, and he was a far-traveled man.

The Kin paid her full death honors, for it was plain she had fought for my life. Children are esteemed among the Kin, who breed thinly, for all our toughness of body and quickness of mind, gifts from Anthea, All Mother.

Thus did I foster with Kin and Second-Kin, close to Ort, Lari's cubling, though he was quicker to find his feet and forge for himself. However, I mind-spoke all the beast ones, and tongue-spoke the Kin; thus all accepted me fully.

Before I passed my sixth winter I had my own team of trained ones, Ort as my seconding. I was able to meet the high demands of Gamer, for he accepted only the best performers.

Because I was able so young, the clan prospered. Those not of the blood seemed bemused that beasts such as orzens and fal, and quare, clever after their own fashion, head-topping me by bulk of bodies, would obey me. Many a lord paid good silver to have us entertain.

Nor had we any fears while traveling, such as troubled merchant caravans that must hire bravos to their protection. For all men knew that the beasts who shared our covered wagons, or tramped the roads beside us were, in themselves, more formidable weapons than any men could hope to forge.

Once a year we came to Ithkar Fair—knowing that we would leave with well-filled pouches. For Garner's shows were in high demand. Lords, even the high ones of the temple, competed in hiring us.

However, it was not alone for that profit we came. There were dealers who brought rare and sometimes unknown beasts—strange and fearsome, or beautiful and appealing—from the steppes of the far north or by ships plying strange seas. These we sought, adding to our clan so.

Some we could not touch with the Calling, for they had been so mishandled in their capture or transport as to retreat far behind fear and hate, where the silent speech could not reach. Those were a sorrow and despair to us all. Though we oft times bought them out of pity, we could not make them friends and comrades. Rather did we carry them away from all that meant hurt and horror and sung them into peace and rest forever. This also being one of the duties Anthea, All Mother, required of us.

I was in my seventeenth year, perhaps too young and too aware of my own powers, when we came that memorable time to Ithkar. There was no mandate laid upon me to mate—even though the Kin was needful of new blood— but there were two who watched me.

Feeta's son by Garner—Wowern. Also there was Sim, who could bend any horse to his will, and whose riding was a marvel, as if youth and mount were of one flesh. Only to me my team was still the closer bond, and I felt no need to have it otherwise.

The fair-wards at the entrance hailed us as they might some lord, though we scattered no gold. From his high seat the wizard-of-the-gate, ready to make certain no dark magic entered, broke his grave mask with a smile, waved to Feeta, who also makes magic, but of a healing kind. Our weapons were few and Garner had them already sheathed and bundled, as well as the purse for our fee ready, so there was no waiting at the barrier.

We would pay a courtesy visit to the temple later, but, since we were not merchants dealing in goods, we made only a silver offering. Now we pushed on into that section where there were beasts and hides, and all that had to do with living things. Our yearly place was ready for us—a fair-ward waiting, having kept that free for our coming. Him we knew, too, being Edgar, a man devoted to Feeta, who had cured his hound two seasons back. He tossed his staff in the air to pay us homage and called eager questions.

We all had our assigned tasks, so we moved with the speed of long practice, setting up the large tent for the showing, settling in our Second-Kin. They accepted that here they must keep to cages and picket lines, even though this was, in a manner, an insult to them. But they understood that outside the Kin they were not as clan brothers and sisters, but sometimes feared. I know that some, such as lly, the mountain cat, and Somsa, the horned small dragon, were amused to play dangerous—giving shudders to those who came to view them.

I had finished my part of the communal tasks when Ort padded to me, squatting back on his powerful hindquarters, his taloned forepaws lightly clasped across his lighter belly fur. His domed head, with its upstanding crest of stiff, dark blue fur, was higher than mine when he reared thus.

"Sister-Kin . . ."—the thoughts of beasts do not form words, but in the mind one easily translates—"there is wrong here. . . ."

I looked up quickly. His broad nostrils expanded, as if drawing in a scent that irked him. Our senses are less in many ways than those of the Second-Kin, and we learn early to depend upon what they can read by nose, eye, or ear.

"What wrong, Brother-Kin?"

Ort could not shrug as might one of my own species, but the impression of such a gesture reached me. There was as yet only simple uneasiness in his mind; he could not pin it to any source. Still I was alerted, knowing that if Ort had made such a judgment, others would also be searching. Their reports would come to those among the Kin with whom they felt the deepest bond.

The Calling we did not use except among ourselves and the Second-Kin—and that I dared not attempt now. But as I dressed for fairing, I tried to open myself to any fleeting impression. A vigorous combing fluffed out hair usually banded down, and I placed on midforehead the blue gem I had bought at this same fair last year, which adhered to one's flesh, giving forth a subtle perfume.

Ort still companied me. Mai, Erlia, and Nadi, the other girls, were in and out of our side tent. But there was no light chatter among us. The tree cat, that rode as often as was possible on Nadi's shoulder, switched its ringed tail back and forth, a sure sign of uneasiness, and Mai looked abstracted, as if she were listening to something afar. She was like Sim with horses, though also she had two Fos deer from the mountain valleys in her team.

It was Eriia who turned from the mirror to face the rest of us squarely.

"There is ..." She hesitated for a moment with her head suddenly to one side, almost as if she had been hailed. Still facing so, she added, "There is darkness here— something new."

"A distress Calling?" suggested Mai, her face shadowed by concern. She faced that portion of the fairgrounds where dealers in beasts had their stands and where we had found those in pain and terror before. Erlia shook her head.

"No Calling—this rather would hide itself—" She brushed her hand across her face as if pushing aside an unseen curtain that she might sense the better.

She was right. Now it reached me. There are evil odors to sicken one, and evil thoughts like dirty fingers to claw into the mind. This was neither, yet it was there, a whiff of filth, an insidious threat—something I had never met before. Nor had these, my kinswomen, for they all faced outward with a look of questing.

We pushed into the open, uneasy, needing some council from any who might know more. Ort snarled. The red glare of awakening anger came into his large-pupiled eyes, while the tree cat gave a yowl and flattened its ears.

Wowern, his trail clothing also changed, stood there, his hand resting on the head of his favorite companion, the vasa hound that he had bought at this same fair last year—then a slavering, fighting-mad thing who had needed long and patient handling to become as it now was. That, too, was head up, sniffing, as Wowern frowned, his hand seeking the short knife that was all fair custom allowed him as a weapon. As we joined him he glanced around.

"There is danger." The vasa lifted lip in such a snarl as I had not seen since Wowern had won its trust at long last.

"Where and what?" I asked. For I could not center fully on that tinge of evil. Sorcery? But such was forbidden, and there was every guard against it. Not only was there a witch or wizard by every gate to test against the import of such, but those priests who patrolled with the fair-wards of frequent intervals had their own ways of snifling out dire trouble.

Wowern shook his head. "Only ... it is here." He made answer, then added sharply, "Let us keep together. The Second-Kin"—once more his hand caressed the hound's head—"must remain here. Garner has already ordered it so, for Feeta urges caution. We may go to the dealers, but take all heed in our going."

I was not so pleased. All of us usually spread out and explored the fair on our own. Within the breast pocket of my overtunic I had my purse, and I had thoughts on what I wanted to see. Though first, of course, we would visit the dealers in beasts.

Heeding orders, we moved off as a group, Sim joining us. Nadi set the tree cat in its own cage, and Ort returned reluctantly to the tents. I felt the growth of uneasiness in him, his rising protest that I go without him.

There were other beast shows along the lane where our own camp had been set up. One was manned by the people from the steppes who specialize in the training of their small horses. Then there was a show of bright-winged birds, taught to sing in harmony, and at the far end, the place of Trasfor's clan—no bloodkin to us, yet of our own race. There we were hailed by one hurrying into oiir path.

Color glowed on Erlia's cheeks when he held out hands in a kinsman's welcome.

"Thasus!" she gave him greeting. I believed that this was something she wished and was sure would happen. By the light in his golden eyes, she was right.

"All is well?" He broke the gaze between the two of them, speaking to all of us as if we had parted only yesterday. "The All Mother has spread her cloak above you?"

Wowern laughed, giving Erlia a tiny push toward Thasus. "Over this one at least. You need have no fear for her, brother."

Erlia did not respond to his gentle attempt at teasing. Her head turned away and on her face lay again a shadow of distress. I had caught it, also, stronger, more determined —that echo of darkness and all evil.

This time it was as if I had actually picked up a foul scent—the kind that clung to swamps, places of death and decay ruled by tainted water. Then it was gone, and I wondered if I had only made a guess without foundation. There are those who sell reptiles and crawling things, yes. But they are set apart from our beasts and have their own corner. One which I, for one, did not spend time in exploring. Yet I was sure this was no stench of animal or of any living thing—

It was gone as quickly as it had come, leaving only that ever-present uneasiness. Still, I dropped a little behind and tried in a very cautious way—not really Calling—to pin upon that hint of evil.

"What is with you, Kara?" Wowern matched his stride to mine.

"I do .not know." That was true, yet deep within me something stirred. I was certain that never before had this unknown touched me. Still. . .

Once again I caught that rank stench. It was stronger, so that I wavered—and, without being aware of what I did, steadied myself by a touch on Wowern's arm. He, in turn, started as might a horse suddenly reined in.

"What—" he began again as I swung halfway about to face an opening between two smaller stalls.

"This way!" As certain as if a Calling drew me, I pushed into that narrow opening, heedless whether the rest of the Kin followed or not.

Ahead was a second line of booths fronting another lane. From these came the chatter of smaller animals, squawks and screams of birds. This was the beginning of the area where merchants and not showmen ruled. Yet it was toward none of these that that trace of need—for need did lie beneath the overlayer of evil—drew me.

I entered the section I had always hitherto shunned— that portion of the mart where dealers in reptiles and scaled life gathered. Dragons I knew, yes, but they are warm-blooded in spite of the scaled bodies and in their way sometimes far more intelligent than my own species. But the crawlers, the fang-jawed, armor-plated creatures, were to me wholly alien.

"What—" Again Wowern broke my preoccupation. I threw out a hand, demanding silence.

The afternoon was nearly spent. Flares outside booths and stalls blazed up—adding their acrid odor—not enough to cover the ill smells of the wares. A deep, coughing bellow drowned out whatever protest my companion might have uttered. Whether the others of our company still followed I did not know nor care.

I stood before a tent perhaps a third the size of ours. But where the leather and stiff woven walls we favored were brilliantly colored, gay to the eye, these walls were uniformly a sickly gray, overcast with a yellow that made me think of decay and pustulant nastiness.

Over the tent-flap the light of a torch brought to life a device such as might be the mark of a noble house. However, even when one stared directly at this (it was as dull as tarnished and unkempt metal) it was difficult for the eye to follow its convolutions. This might be a secret seal only a mage could interpret.

Shivering, I looked away. There was an impression of dark shadow angling forth, as might the tentacle of an obscene creature questing for prey. Still, I must pass under, for what I sought lay within.

No merchant stood to solicit buyers. Nor was there any glow of lamp. What did issue as I walked slowly, more than half against my will, toward that dark opening was the effulgence of a swampland wherein lay evil and death.

There was light after all—a greenish gleam flaring as 1 passed the flap. I could see, fronting me, a short table of the folding sort, some lumpish stools, like frozen clots of mud. Around the walls of the tent were cages, and from them came a stealthy, restless rustling. Those within were alert ... and dangerous.

I had no desire to walk along those cages, peer at their occupants. I had no wish to be here at all. Still, my body—or an inner part of me—would not allow me back into the open air. Out of the gloom, which pooled oddly in corners as if made up of tangible hangings, emerged a figure so muffled by a thickly folded robe, so encowled about the head, that I could not have said whether I fronted man or woman.

The green glow that filled the tent, except in those shadowed corners, appeared to draw in about the newcomer, forming an outline, yet not illuminating to any great extent. There was an answering glow of dullish light from the breast of the robe. A pendant rested there—gold, I thought, but dull. I could make out (as if it were purposefully expanding and drawing color just to catch my eyes) the shape of a head—beautiful but still evil. The eyes were half-covered with heavy lids, only I had the fancy that beneath was true sight, so I was being regarded by something reaching through the metal—regarded and measured.

"Lady." The voice from beneath the hood, shaped by lips I still could not see, was clear. "You would buy." It was not a true question, rather a statement, as if any bargain we might make was already concluded.

Buy? What? I wanted nothing from any of those cages whose contents I still could not see. Buy? ...

My gaze was pulled—away from the robe-hidden seller—until I looked over his or her left shoulder. There was one cage apart from the rest, a large one. And within it—

As one walks in one of those troubled dreams wherein one is compelled to a task one dreads, I moved forward, though I still had enough control over my shivering body to make a wide circle, not approaching either that table or the one who stood by it.

The cage was before me and here the shadows were thick curtains—the light did not reach. Nor could I discern any movement. Yet there was life there—that I knew.

I heard a sound from the merchant, out of my sight unless I turned my head. Did he speak or call? Certainly what he uttered was in no tongue I knew.

In the air above the cage appeared a ball of sickly yellow which cast light—no flame of any honest torch.

A creature crouched low upon the floor of the cage, so bent in upon itself that at first it was difficult to see any exact shape. Its skin was a dirty gray, like the tent walls, not scaled, but warty and wrinkled, hanging in folds. There were four limbs—for now it uncoiled to rise. When it reached its full height, it stood erect on hind limbs, its feet webbed and flat. It was taller than I, matching Wowern's inches.

There was a thick growth of ugly yellow wattles about the throat and a ragged comb-crest of the same upon its rounded head. The forelimbs reached forward as massively clawed digits closed about the bars of the cage, scratching along the metal. There was no chin, rather a wide mouth like that of a frog, above that a single slit, which must serve it as a nostril. Only—the eyes ...

In that hideous nightmare of a face they were so startling that they brought a gasp from me, for they were a clear green—like wondrous gems in an ugly and degrading setting. Nor were the pupils slitted as one would expect in a reptile or amphibian—but round, somehow as human as my own. Also ... in them lay intelligence—intelligence, and such pain as was a knife thrust into me when our gaze locked.

What the creature was I could not tell. Certainly I had never seen its like before. A flutter of movement to my left, and the robed merchant moved closer. From one of those long sleeves issued a hand as pale as that of any fine lady, very slender and long of finger. This waved in a surprisingly graceful gesture toward the still silent captive.

"A rare bargain, lady. You shall not see the like of this perhaps again in your lifetime."

"What is it—and from where?" Wowern's voice was loud and harsh. He moved in upon my right and I could sense his growing uneasiness, his desire that we both be away from this hidden-faced one and his or her strange wares.

"What is it?" the other repeated. "Ah. It is so rare we have not yet put name to it. From where? The east."

Then I felt cold. All who roved knew what lay to the cast—that swampland so accursed that no one ventures into it—about which all kinds of evil legends and tales have been told for generations.

"A bargain," the merchant repeated when neither of us made comment. "All know of the Quintka—that you delight in your trained beasts—that you seek ever new ones to add to your company. Here is one which will bring many flocking to see it. It is not stupid, I think you can train it well."

Those green eyes—how they demanded that I look Upon them! That feeling of pain, of sorrow so deep that there were no words to express it—flowed from them to me.

"It is a monster!" Wowern caught my arm in a grip so tight that his nails near scored my flesh. I could sense fear rising in him—not for himself but for me. He strove to 'pull me back a step or two, meaning, I understood, to take me out of this place.

"Five silver bits, lady."

The caged creature made no sound; I felt rather than saw its compelling gaze shift a fraction. It looked now to the robed one, and within those green eyes was a flare of deep and abiding hatred. Within me arose an answer.

Those eyes, did they trouble me with some fleeting memory? How could they? This was an unknown monster. Yet at that moment this feeling of emotion was as much a true Calling as if mind-words passed. Our meeting was meant to be.

I brought out my purse. Wowern's hold on me tightened. He protested fiercely but I did not listen. Rather I jerked free, and, without the usual bargaining, I counted forth those bits. Not into that long-fingered graceful hand; rather, I turned and tossed them on the tabletop. I wanted no close contact with the merchant. Nor did I want to linger here, for it seemed those heavy shadows reached farther and farther, drawing out of the tainted air any hint of freshness, leaving me breathless,

"Loose—" I got out that part order, past a thickening of my throat, not sure that even a Quintka could control such a creature. Still, when I met again those eyes so wrongly set in that hideous face, I was not afraid.

The robed one uttered a queer sound, almost as if he or she had choked down jeering laughter. There was no move to draw any bolt or bar locking that cage. Instead, the slender hand went to the pendant lying heavy on the robe, fingers closed tightly about that, hiding the beautiful, vile face from view.

There sped a puff of darkness from that hand— thrusting outward to the bars of the cage. The creature had retreated, standing with shoulders a little hunched. I smelled a sickly sweetness which made my head swim— though I stood well away from that black tongue.

It wreathed about the bars and they were gone. For a long moment the creature remained where it was. From all the other cages about uprose not only a frenzied rustling, as if the other captives aroused to demand their own freedom, but also gutteral grunts and croakings, hissings—

That thing I had so madly purchased shambled forward. I was aware, without turning my head, that the robed one moved even more quickly, retreating into a deeper core of shadow. That retreat pleased me, made me less aware of my own recklessness. Did this merchant fear the late captive? If so, no such fear was mine. For the first time I spoke to the monster, using the same firm tone I would with any new addition to my team. "Come!"

Come it did—treading deliberately on hind legs as if that came naturally, its taloned paw-hands swinging at its sides. I turned, sure within myself that where I went it would follow.

However, once outside that tent I paused, for whatever compulsion had gripped me faded. Also, I realized that I could not return to our own place openly. Even though the twilight gathered in, this creature padding at my heels, as if he were a well-trained tree cat, was far too obvious and startling. Though it was often the custom for one of the Quintka to parade a member of his or her personal team through the fair lanes as an inducement for a show, none of us had ever so displayed a creature like unto this.

Wowern wore his trainer's cloak hooked at the throat, thrown back over his shoulders. I had not brought mine. The feeling that we must attract as little attention as possible made me turn to him. There was no mistaking the frown on his face, the stubborn set of his chin.

"Wowern . . ." It irritated me to ask any favor, still, I was pressured into an appeal. "Your cloak?"

His scowl was black, his hand at the buckle of that garment, as if to defend himself against my snatching it from him. Behind him the monster stood quietly, his eyes no longer on me, for his bewattled head was raised as he stared at the device above the tent-flap door.

At that moment I swayed. What reached me was akin to a sharp blow in the face, a blast of raw hatred so deep—so intense—as to be as sharp as a danger Calling! Wowern must also have been struck by it. Hand to knife hilt, slightly crouching, he swung half-about. ready to defend himself. Only there was no attack, just the creature, its arms still dangling loosely at its sides, staring upward.

His eyes narrowed, his scowl fading into something else, an intentness of feature as if he strained to listen, Wowern surveyed that other. Then, with his left hand, for he still kept grip upon the knife, he snapped open cloak buckle and swiftly spun the folds of cloth about the creature in such a skillful fashion that its head was covered as well as its body to the thick and warty-skinned thighs.

"Come!" He gave the order now. Again he seized upon my arm with a grasp I could not withstand, propelling me forward to the opening of the same narrow side lane that had brought us here, taking no note of the muffled creature, as if he were entirely certain it would follow. Thus we came back to the place of the Kin, Wowera choosing our path, which lay amid such pockets of shadow as he could find. I allowed him this leadership, for I was in a turmoil within myself.

I realized that we two had been alone. The others of our company must have gone on when I had been seized by the need to hunt out the dismal, shadowed tent. Which was good—for the moment, I could have made no real explanation of why I had done what I did.

Ort met me at the edge of our stand, his head forward, voicing that anxious, half-growling sound he always used when I left him. Sighting what accompanied us, he snarled, lifting lip to show gleaming teeth, his claws well extended as he brought up both paws in the familiar stance of challenge. Before I could send a mind-message, his growl, which had risen to a battle cry, was cut off short. I saw his nostrils expand, though since we had left that foul tent I had not been aware of any odor from the creature.

Now Ort fell back, not as one afraid, rather as one puzzled, confronted by a mystery. I picked up the bewilderment which dampened his anger, confused him to a point I had never witnessed before.

"Brother-Kin," I mind-reached him. Though the muffled monster betrayed no sign of anger, I wanted no trouble. Ort had never been jealous of any of my team. He knew well that he was my seconding, that between the two of us there was a close bond which no other could hope to break. "Brother-Kin, this is one who ..." I hesitated and then plunged on, because I was as sure as if it had been told jne that I spoke the truth. "Has been ill-used—"

Ort shuffled his huge hind paws; his eyes were still on the creature as now Wowera caught his cloak by the edge and whipped it away from that ugly body, plainly revealed in the torchlight.

The monster made no sound, but its bright eyes were fast on Ort. I saw my Brother-Kin blink.

"Sister . . ." There was an oddness in Ort's sending. "This one—" His thought closed down so that I caught nothing more for a long moment. Then he came into my ~mind more clearly. "This one is welcome."

The stranger might be welcome to Ort, but with Gamer and the rest of the clan it was a different matter. I was told that I had far overstepped the bonds of permissiveness, taking upon myself rights none had dared before. I think that Garner would have speedily dispatched my monster to his former master and cage, save that Feeta, who had been silently staring at my purchase, broke into his tirade. The rest of the clan had also been facing me accusingly, as if, for the first time in my life, they judged me no Kin at all.

"Look to Ort," Feeta's voice arose, "to Ily, Somsa—" She pointed to each of the Second-Kin as she spoke.

We stood in that lesser tent where our smaller teammates were caged, or leashed, according to fair custom. What she made us aware of was the silence of all those four-footed ones, the fact that they regarded the newcomer round-eyed—and that they had broken mind-link with us.

Garner paused in mid-word, to stare from one to another of those seconding our teams. I felt his thought, striving to establish linkage. The flush of anger faded from his face. In its place came a shadow of concern, which deepened as he beat against stubbornly held barriers.

Feeta took a short pace forward, raising her right hand so that her forefinger touched the forehead of the monster at a point between its brilliant eyes. Then she spoke to me alone, as if all there were only the three of us—healer, monster, and I.

"Kara.. ."

I knew what she summoned me to do. In spite of the deep respect and obedience she could always claim from me, I wanted to refuse. Such a choice was denied me. Was it the power of those green eyes that drew me, or the weight of Feeta's will down-beating mine? I could not have said as I went to her, taking her place as she moved aside. My hand came up that my finger, in turn, filled the place where hers had touched.

There was a sick whirling, almost as if the world about me was rent by forces beyond my reckoning. Also, I sensed once more that overshadow of faint memory out of nowhere. This was like being caught in a vast, sticky web— utterly foul, utterly evil, threatening every clean and decent thought and impulse. Entrapped I was, and there could be no loosing of that bond. No! There was also resistance, near beaten under, still not destroyed.

The net was not mine. That much I learned in a breath or two of time. Just as that stubborn, near despairing resistance was not born from any strength within me!

Danger—a murky vision of thick darkness, within which crawled unseen perils all so obscenely alien to my kind as to make the very imagining of them fearsome. Danger—a tool, a weapon launched, set to strike—but a tool that could turn in the user's hand, a weapon whose edge might well cut the wielder.

"What threatens us?" I demanded aloud, even as I also hurled that thoughtwise, threading it into that wattled head through my touch.

I felt Feeta catch my free hand, hold it in a tight grip between both of hers. From the creature came a pulsating flow—sometimes sharp and clear, sometimes fading, as if the one who sent it must fight for every fraction of warning.

Evil, dark, strong, rising like a wave— There lurked within that darkness the beautiful face of the pendant. It leered, slavered, anticipated—was arrogantly sure of victory. I heard a gasp from Feeta—a single word of recognition.

"Thotharn!”

Her naming made my vision steady, become clearer. Names are potent things, and to call them aloud, our wise people tell us, can act as a focus point for power.

Thotharn I might not know, though of him I had heard, uneasy whispering for the most part, passed from one traveler to another as veiled warnings. There were the Three Lordly Ones upon whose threshold Ithkar stood, there were other presences within our world which my kind recognized and paid homage to—did not we look to the All Mother? But Thotharn was the dark, all that man feared the most, shifting westward from swamplands into which no man, save he be outlawed and damned, dared stray.

It is an old, old land—the swamp country. We who tread the roads collect tales upon tales. It is said there was once a mighty nation in the east—greater than any existing today, when small lordlings hold their own patches of land jealously and fight short, bitter wars over the ownership of a field or some inflated pride. The north was ravaged when I was a small child, by the rise of a conqueror who sought to bring diverse holdings under one rule. But he was slain, and his patchwork of a kingdom died with him, by blood and iron.

Only in the east was no tale of a lordling with ambition. No—there was far more, a rulership that impressed itself on all the land and under which men lived in a measure of peace, no lord daring then to raise sword against his neighbor. There came an end, and tradition said this end was born of evil, nourished in evil, dying evilly, even before the Three Lordly Ones came to us. With the breaking of this power the land fell into the depths of night for a space. All manner of foulness raved and ravaged unchecked. Was Thotharn a part of that? Who knows now?

But in these past few years rumor spread again his name— first in whispers, and then openly.

Thotharn's priests walked our roads. They did not preach aloud, as did the friars or the wise ones who serve All Mother, striving thus to better the lives of listeners. Nor did they shut themselves into a single temple pile and impress their weight of service demands as did those who outwardly acclaim the Three Lordly Ones. They simply walked, and were ... while from them spread an unease and then a drawing—

From the creature I touched flared red rage, strong enough to burn my mind. Thotharn—yes! That name awakened this emotion. But it was against the dread lord of shadows that that blaze was aroused. Whatever this creature might be, he was no hand of the east.

No hand. It caught at my turn of thought, seized upon it, hurled it back to me, changed after a fashion. Obey the will of Thotharn—no, not that, ever! When I acknowledged that fraction of half appeal, that need to make clear what lay inside the other's brain and heart, there was a swell of triumph through the sending—a quick flare like a shout of "Yes, yes!"

I spoke aloud again. Perhaps some part of me wanted to do so, that I make very sure of what I learned.

"They believe you serve them? ..."

Again a burst of agreement. There is this about mind-send: a man may cloak his values and his desires when he uses words, but there can be no hiding of the truth while sending. Any barrier becomes in itself a warning and injects suspicion. That this hideous thing out of the swampland could hide from me in thought was not to be believed. But, knowing this, why then would any follower of Thotharn—such as the robed merchant must surely be—thrust upon a Quintka possessing sending powers a creature so easily read?

That thought, also, was picked up. The churning within the other became chaotic in eagerness to answer.

Thoughts were so intermingled, came so swiftly, that I could not sort one from the other. I heard far off, as if she were now removed from me, though still our hands were locked, a gasped moan from Feeta. I guessed that it was only our linkage, her power and mine together, that made this exchange possible at all.

There were scraps of information—that the robed one of Thotharn knew of the Quintka, had marked them because of their far traveling, the fact that they were readily welcome in lords' keeps, even the temples—that the people who gathered for our showings were many in all parts of the land. Where a wandering priest or priestess of suspect learning could not freely go, one linked with us might penetrate. However, the swamplanders did not truly know the Quintka. They accepted us as trainers of beasts, not realizing that, to us in our own circles, there was no Kin and beast—two things forever separated—rather there was Kin and Second-Kin linked by bonds they did not dream existed.

This one had been prepared (the plan had been a long time in the making—and it was their first such) to be sent out as a link between their great ones, who did not leave the swamp, and the world they coveted so strongly. The first—there would be others. The robed one I had dealt with—I learned in that half-broken communication with my purchase—had believed 7 was under the influence of Thotharn's subtle scents and pressures when I bought it—that when I left, already I was a part, too!

"Why do you betray so easily your masters?" I strove to find some flaw in this flood of explanation. "You were made for what you do, yet now you freely tell us that you are a thing designed to be all treachery and betrayal—"

"Made!" Again a flare of intense anger—so painfully projected into my mind that I flinched and near dropped my finger contact. "Made!"

In that bitter repetition I understood. This thing, in spite of all its grotesque ugliness, was near mad from the usage it had received. It had lain under Thothara's yoke without hope—now it took the first opportunity to strike back, even though any blow it might deliver could not be a direct one. Perhaps it also had not realized the Quintka had their own defenses.

It was even as I caught this that there dropped a sudden curtain of silence. But not before, it seemed to me, a whiff of foul air blew between me and this purchase of mine. The green eyes half closed, then opened fully. In them I read appeal—an agony of appeal.

Feeta loosed her grip, caught at my wrist, jerking me back from that touch which had brought us such knowledge.

"What is it?" I rounded upon her.

"They are questing—they might learn," she half spat at me. Never had I seen her so aroused. "Is that not so? Blink your eyes if I speak the truth!" She spoke directly to the creature.

Lids fell over those green eyes, rested so for a breath as if to make very sure that we would understand, then arose again.

I heard a swift, deep-drawn breath from Gamer where he stood, feet a little apart, as one about to face an enemy charge. Feeta spoke without turning her eyes from the swamp thing.

"You mind-heard?"

Garner bared his teeth as Ort might do. "I heard. So these crawlers in the muck would think to so use us!"

"To plan is not to do." I did not know from whence those words came to me but I spoke them, before I addressed the swamp dweller.

"These you serve, do they have a way of setting a watch upon you? Blink in answer!"

Again, deliberately those eyes closed and reopened.

"Do they know of our linkage? Blink twice if this is not so." I waited, cold gathering within me, fearing one answer, but hoping for another. That came—two measured blinks.

"So . . ." Garner expelled breath in a mighty puff. He dropped a hand on Feeta's shoulder and drew her to him. The tie between them was so old and deep that I did not wonder he had been able to link with her during that exchange. "Now what do we do?"

I had one answer, though whether he would accept it or not I could not tell. "To return this would arouse their suspicions, lead them to other plans."

He snorted. "Think you that I do not understand that?" He regarded the creature measuringly. Then he made his decision.

"This one is yours, Kara. Upon you rests the burden."

Which, of course, was only fair. , Garner and the others left me with the self-confessed spy of evil. Only Second-Kin—Ort, the rest of the beasts— remained. They continued to watch the stranger with unrelenting stares.

We had no cage large enough to accommodate the being, and somehow it did not seem fitting to set a rope loop about its neck, tether it with the four-footed ones. Where was I to keep it? Soon would come time for the night shows, and it should be under cover before our patrons came to look at the animals as was the regular custom.

Ort answered the problem with action that surprised me greatly. He padded to the baskets of act trappings set along one side of the tent, came back to me, a wadding of cloth in his forepaws. I shook out a cape with a hood, old and worn, which had been used to top and protect the stored "costumes" our teams wore. It was a human garment and the folds appeared adequate to cover the creature.

Wowern had already taken back his cloak; now I flung this musty-smelling length about the thing's shoulders, fastened the rusty throat buckle. To my astonishment the creature, as if it were indeed a man and not grotesque beast, used its forepaws to pull the hood up over its misshapen head, well forward so that its ugliness was completely hidden. I could almost believe that I fronted a man—not a monster.

Ort chirped, one of those sounds my human throat could not equal. Our disguised one swung about, stumping after my seconding, out of the tent and into the shadows beyond. With an exclamation I hurried after.

Ort apparently had no such thing as escape in mind, nor did the other, who was certainly powerful enough to leave if it wished, deviate from the path shown it. Rather, it squatted down at the end of the row where our mounts were tied, concealed behind the bales of hay now stacked as a back wall. In those shadows the dull gray of the cloak was hidden, one would not have known that anything sheltered there.

The horses and ponies had stirred uneasily at first, but Ort paced down their line, giving voice to that soothing throat hum which he had used many times over to reassure nervous beasts. They accepted this newcomer because of his championship.

I hurried to change clothing, catching up some cold food to eat between the doffing of one robe, the donning of another, the fastening of buckles, the setting of sham jewels about my throat, wrists, and in hair strings. Nadi and Erlia were already prepared and on their way to lead forth their teams, but Mai stood before our mirror applying a thicker red to her lips.

"What do you plan to do?" she asked bluntly. "To carry with us a spy—even though it seems to have no liking for its true master—that is to endanger all of us. Why do you bring this upon us, Kara?" There was no softness in her voice, rather hostility in the eyes that met mine within the mirror.

"I—I had no choice." To me that was truth. I had clearly been drawn to the merchant's booth; once there I had been enspelled.. . . Enspelled? I shivered, the cold was well within me now and I could not rid myself of it.

"No choice?" She was both scornful and angry. "This is foolishness. Would you say you are englamored by this bestial ugliness out of the dark? Ha, Kara, you cannot expect the rest of us to risk its presence."

She swept away and I knew that she gave a truthful warning. Those of the clan would not long accept—even at Gamer's and Feeta's bidding, if I could depend upon that—this addition to our party. I did not want it, either. I—

Yet I had paid that silver without a question. Unless .. . Again I shivered and stood very still, my hands clasped tightly on the handle of my team leader's wand. Unless there was something in me which that robed one had been able to touch, to tame to his or her will, even as I lead my team! If that were so, then what flaw lay inside me that evil could reach out so easily and twist to its own usage? At that moment I knew fear so sharp it made me waver where I stood, throw out a hand to the edge of the mirror table and hold fast, for it seemed that the very earth moved under my feet.

I heard the thump of drums in the show tent. Habit set me into motion without thought. Nadi was dancing with her long-legged birds now—next I must be ready with my marchers. I staggered a little, still under the touch of that fear. Ort awaited me, his hand drum slung about his thick neck. Behind him, in an ordered row, were Oger, Ossan, Obo, Orn—just as they had been for months and years. Tall all of them, their talons displayed in order to astound the audiences, their bush combs aloft, and their long necks twining back and forth to the beat of the drums.

Nadi's music faded. She would be issuing from the other side of our stage. I breathed deeply twice, steadying my nerves—putting out of my mind with determination all except that which was immediately before me—the need to give my part of the show.

We had finished the first appearance of the evening and Garner was talking to several who wore the shoulder ribbons and house marks of lords, making arrangements for private performances. Those would be steady for us all during the two ten-days we were in Ithkar. However, another stood in the lesser light just at the edge of the torch beams as if waiting his or her turn at bargaining. Enveloped in a cloak, it might well be a woman—and of that I was sure when a hand bearing a ring-bracelet came out of hiding to draw closer the cloak. She made no effort to push forward until Garner had finished and the others were gone. I saw her speak and Garner raise his head, stare across the crowded yard between our tents where fairgoers came to see closer our teammates. He looked at me, nodded, and I could not escape that silent order.

So I went to join him and the other. Her gem-backed hand touched her hood, pushing it back a little. I saw a face, deeper brown in color—some southern-born lady, I thought. Her features were thin and sharp, with an impatient line between her straight brows. No beauty—but one who was obeyed when it pleased her to give orders.

"Speak with this one." Garner was also impatient. "What we know is her doing." He left abruptly. The lady regarded me as 1 would a beast unknown—curious, perhaps. However, there was a sting in that survey. I lifted my chin and eyed her as boldly back.

"You made a purchase." She spoke abruptly. There was a slurring in her speech new to me. "It was one not meant for you."

"I was asked a price and I paid. The merchant seemed satisfied," I returned. This might be the answer to our problem. If she wanted the swamp dweller, then let her have him. But I would not strike any bargain until I knew more. At this moment it seemed to me that I saw between the two of us those wide green eyes.

"Paugh!" Her lips moved then as if she would spit, as might any common fair drab, highborn though she seemed. "That merchant exceeded his instructions. I have come" —a second hand appeared from beneath her robe, in it a purse weighing heavy by the look—"to buy what is rightfully mine. Where is he?"

"Safe enough." I made no move to take that purse. The hand holding it had come fully under the light and on the forefinger I saw the ring—the same smiling face of the merchant's pendant formed its bezel.

"Summon him." She moved a little, almost as if she wanted to be well away from us. "Summon him at once!"

Had they then learned, these followers of Thotharn, that the swamp creature had betrayed their purpose, and so were eager to reclaim him? What would be his fate at their hands? I knew that Garner would report to the temple all we had learned. These could reclaim the creature, slay it, and deny all. What proof would we have then that they had tried to move so against the peace of Ithkar?

"I—" Fear I had known, even disgust, when I had made that purchase; still, I would betray no living thing. For the Quintka might not deny refuge to the Second-Kin. Second-Kin—a swamp creature out of the dark land? Yet Ort and the others had made it welcome after their own fashion, and their instincts I trusted.

"Summon him!" Her order was sharp; she waved the bag back and forth so it gave out a clink of metal. It must be well filled with coin. "I give you four—five times what you paid. He is mine—bring him hither!"

I heard the guttural throat sound from Ort and looked over my shoulder. My Brother-Kin led a cloaked shape into the open, the swamp creature. Still, Ort lifted his lips a little, showing fangs, and I knew that what he did was not in obedience to such as she who stood with me, nor even to me. He moved for himself—and perhaps another.

Those who had come to see the animals had passed along—I heard the boom of a gong signaling the second part of our performance and the thud of hooves as the horses moved out into the circular space beyond. We were alone now—the four of us.

"Ran ..." Her voice was far different from that with which she had addressed me. "Ran, I came as I had promised—freedom!" She swung up the purse to give forth again that clinking.

I saw a warty paw in the open, tugging at the hood so it fell free upon his broad shoulders. His nightmare face was clear. She bit her lip and could not suppress the shadow of distaste, near of loathing. She is not, the thought flashed into my head, as good an actress as she believes.

"Take it!" Again she shoved the bag in my direction.

I put my hands behind my back as the green eyes turned toward me. I could not pick up any clear mind-speech, and I dared not touch him to establish linkage. But somehow I felt again that blaze of red rage—not for me, but for this woman.

"I will not," I said firmly. Though I could not find any true reason why—except those eyes.

"You shall!" She thrust her head forward and her hood fell away, her eyes bored into me. Then I saw her gaze change a fraction; she caught her breath. "No. . ." Her voice was a half whisper. "Not that—the blood—"

I am no voice of the All Mother, I wear no robe of the Three Lordly Ones—I am no shaman of any tribe. Still, there awoke in me then something that I had sensed twice before this day—an ancient knowledge. Nor was that of the Quintka. Partly of their blood I might be—yet who knew what other strain my dead mother had granted me?

What I did came in that moment as natural as breathing—I brought forth both hands as I took two quick steps toward my monster. He pawed at the buckle of his cloak and that fell away from him, leaving his nightmare body bare. My hands fell to his shoulders, the roughness of his skin was harsh under mine. He had to bend a little from his height. All that filled the world now were his green eyes—and in them was a flashing light of eagerness, of hope reborn, of pain now fading—

"By the thorn and by the tree,

By the moon and by the sea,

By the truth and by the right,

By the touch and by the sight,

Let that which is twisted,

Straightened be.

That the imprisoned go free!"

I pressed my lips to the slimy cold of his toad mouth. Fighting revulsion—pushing it utterly from me.

When I drew back I cried aloud—words that had no meaning, yet were of power—and I felt that power fill me until I could hold no more. My fingers crooked, bit into his odious flesh. I tore with my nails— The skin parted, as might rotted cloth. As cloak so old that nothing was left but tatters, that skin gave to my frantic hands, rent, and fell away.

No monster, but a man—a true man—as I shredded from him that foul overcovering. I heard a shriek behind me—a keening that arose and arose. Then the man I had freed flung out one arm, to set me behind him, confronting the woman. She had her beringed hand up, held close to her lips, ugly and open, as she mouthed words across the surface of that head-set ring. Frantically she spilled forth spells. His hand shot out, caught hers. He twisted her finger, pulled free the ring, flung it to the ground.

There was a barking cry from Ort. One of his ponderous hind feet swept between the two at ground level, stamped that circlet into the beaten earth.

The woman wailed, then spat in truth, before she fled. Where the ring had been pounded there arose a small thread of smoke. Ort leaned forward and spat in turn, full upon the thread, setting it into nothingness.

"So be it!" A deep voice.

A well-muscled arm swooped, fingers caught up the cloak, once more twisting it about a bare body, but this time a human body. "So be it."

"You are a man—" The power that had filled me vanished as quickly as it had come. I was left with only amazement and a need to understand.

He nodded. Gone from him was all but the eyes— those were rightly his, marking him even through the foulness of the spell. "I am Ran Den Fur—a fool who went where no man ventured, and by my folly I learned. Now . . ." He gazed about him. I saw the cloak move as he drew a deep breath, as if inhaling new life to rid him of the old. "I shall live again—and perhaps I have put folly behind me."

He looked at me with the same intentness as when he had tned to link earlier.

"I have much to thank you for, lady. We shall have time—now—even in the shadow of Thotharn, we still have time."