Review of Iron Cage

by Steven Howell Wilson

January 26, 2018

I’ve never read Norton, which is odd, her being one of the most celebrated science fiction authors of her generation. But I think it’s like this: I started reading SF at a time when Norton was still a relatively new author. By “relatively new,” I mean her books began being published around the time I was born, and I began reading SF at age 8. When I did, I started with Bradbury, Williamson, Clarke and Blish, segued to Asimov and then to Heinlein.

All of these authors, while around the same age as Norton, were published in book format long before she was. Heinlein wrote juveniles beginning in 1948, Asimov published Foundation in 1951, Bradbury published The Martian Chronicles in 1950. Norton was writing in the 1940s, but her work was predominantly featured in magazines. I didn’t have access to SF magazines as a kid. What I had was the school library at a small, private school. The SF collection was more likely to be the tried and true novels of ten years ago than anything up to date.

One exception to the “old guy” list was Alan Dean Foster, whose first novel was published in 1972. He came to my attention because he wrote the Star Trek Logs, and pretty much every movie novelization there was in the SF and horror genres.

Similarly, although he’s one of the “old guys,” Arthur C. Clarke I knew from 2001, which was a movie and a comic book series, and thus more prone to attract a kid’s attention.

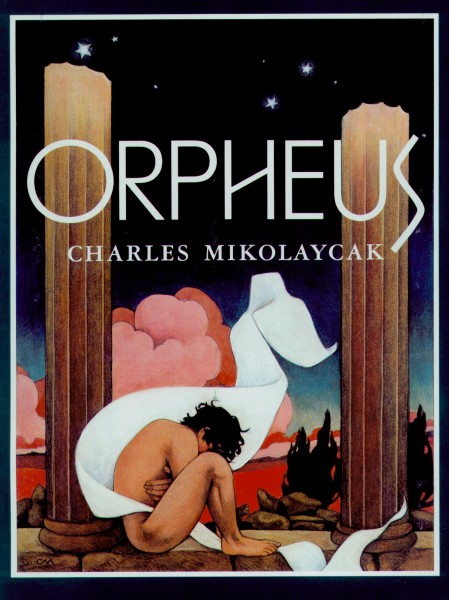

So Norton got neglected on my reading list, even though I recalled the beautiful Charles Mikolaycak covers from the shelves at my local B. Dalton and Waldenbooks. Mikolaycak had a romantic’s eye for the human form, and his cover art for Norton’s books, while understated in color, were eye-catching. Still, at the time I was devouring every Star Trek novel and fanzine there was, which kept me pretty busy, and didn’t leave room for discovering too many new authors. The only other notable authors I can mention from my teens would by John Varley and Vonda McIntyre.

Now, in my fifties, crotchety and dissatisfied with this newfangled thing that the Big Six assures me is science fiction, but that I’m pretty sure is not, I’m catching up on the back list.

And it’s an odd connection that led me to Norton. I’m a huge devotee of mythology, and my introduction, of course, was Greek Myth. Mostly tragic, and the gods are straight-up dicks, but entertaining. At an antique store, I came across a beautiful, painted children’s book about Orpheus. I wasn’t sure I would call it a children’s book, as the nude paintings were pretty much soft erotica, but I bought it because I collect mythology and it was quite beautiful. The artist’s style was familiar, so I Googled him and realized that he had done all those Andre Norton covers in the 1970s. And that led to my V-8 moment: “Oh shit! I forgot to ever read Andre Norton!”

And it’s an odd connection that led me to Norton. I’m a huge devotee of mythology, and my introduction, of course, was Greek Myth. Mostly tragic, and the gods are straight-up dicks, but entertaining. At an antique store, I came across a beautiful, painted children’s book about Orpheus. I wasn’t sure I would call it a children’s book, as the nude paintings were pretty much soft erotica, but I bought it because I collect mythology and it was quite beautiful. The artist’s style was familiar, so I Googled him and realized that he had done all those Andre Norton covers in the 1970s. And that led to my V-8 moment: “Oh shit! I forgot to ever read Andre Norton!”

Now, being me, I had a collection of Norton novels on my shelf. I collect SF whenever it’s cheap or free. Some for me, some so I have a library that future generations can access, because, again, I think most of what the 21st Century has added to SF literature could be safely excised and nobody would know or care. (Sturgeon’s Law applies here, only too well.)

Rutee and her seven-year-old son Jony are human captives of “The Big Ones,” giant, humanoid (we believe) aliens who scooped up a bunch of humans from a colony world in order to experiment on them. When we meet them, Rutee is pregnant, having been raped by a mind-controlled young male at the behest of the Big Ones. They call it “breeding her,” of course. Her husband has been killed because he resisted and could not be mind-controlled. Jony is a telepath who can not only read and send thoughts, but can control the minds of others, human and alien.

Rutee and Jony manage to escape their captors while the laboratory ship is landed on an unknown planet. Rescued by intelligent mammals called “The People,” they thrive for a few years. Rutee gives birth to twins, a boy and a girl, and Jony grows to be a teen. Rutee dies from something resembling flu, but the kids have a safe and nurturing home.

But happily ever after isn’t to be for Jony. He discovers that the planet they live on was once inhabited by humans who enslaved The People. When he discovered this by exploring ruins of the human civilization, The People assume he’s trying to learn about their former masters’ weapons so that he, too, can become a slave master. There’s a heaping helping of racial distrust built into this. Jony is exiled and forced to wear a slave collar.

Then other humans show up, having found the world quite by accident. We learn now that Jony is the child of an Earth colony, but the humans who lived on his adopted world had technology Earth doesn’t know about. When the new visitors try to “rescue” the three kids, they also decide to capture some of The People as specimens, just as Jony himself was once captured by The Big Ones. Jony’s sister Maba fights by his side to free their friends, but their brother Geogee wants to go back to Earth and be a real human. Only Jony has the native ability to awaken the sleeping technology of The People’s former masters.

It seems an insoluble problem, and tragedy looks to be in the offing. But Norton doesn’t take the story to a tragic end. In Jony she has created a hero with an inborn inability to take the life of another intelligent being. Rather than wipe out his enemies—and, honestly, both humans and The People could count as his enemies—he forces a solution that could bring about peace and harmony. Amidst the very spare writing, and showing very little personal history for any of the characters, Norton creates one unique young hero.

This story is bookended by the tale of a family cat who, pregnant and about to give birth, is sent with an asshole of a neighbor boy to be dropped off at the local shelter as her owners are getting ready to move. Instead of taking her to the shelter, he tosses her out the window of a moving car. The parallels are clear

This is a very representative piece of Seventies science fiction. The Seventies had a very specific tone, a combination of equal parts dark, depressing, pacifist, environmentalist and humanist. I’ve written about the depressing aspects before. This story especially shows the animal rights side of the environmentalist movement of the time. In addition, Jony’s inability to murder shows the humanism and pacifism. And it’s all wrapped up in a lot of darkness—rape, animal abuse, slavery. And yet, unlike the tone of some of today’s morality plays, it’s never shrill or preachy. It just is the story it is, fearless, economical, and gripping.