Now Available in Print and Kindle at Amazon

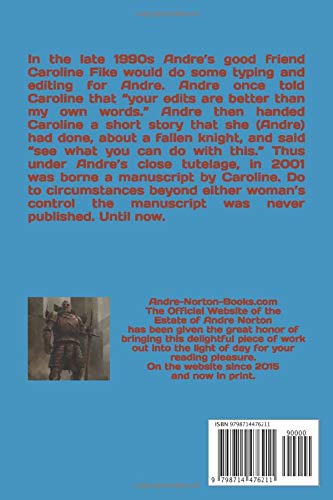

Back in the late 1990s Andre’s good friend Caroline Fike would do some typing and editing for Andre. Andre once told Caroline that “your edits are better than my own words.”Andre then handed Caroline a short story that she (Andre) had done, about a fallen knight, and said “see what you can do with this.” Thus under Andre’s tutelage, in 2001 was borne a manuscript by Andre and Caroline. Do to circumstances beyond either woman’s control the manuscript was never published. Andre-Norton-Books.com has been given the great honor of bringing this delightful piece of work out into the light of day for your reading pleasure. We also have the original short story done by Andre. And so, without further ado, I tell you now, if you click on the title’s below you will travel to the world of “Hart” the fallen knight. Enjoy, for I sure did!

Rusted Armor is now in print. Because of this we are only posting the short story and an excerpt in the way of chapter one. In support of this website, please purchase from Amazon.com. You will NOT be disappointed. All proceeds go to maintaining this site.

Rusted Armor

A Short Story by Andre Norton

Daylight shone in a ragged splotch around him. One of the forest giants brought to earth in a spring storm, tearing with it the lesser trees, thus had opened a space to the sky. He half lay his back against the fallen trunk.

The cut above his eye pained him, gift of a villain having both with a stone and power is the arm. The stench came from his ragged surcoat, clotted with dung.

First he had been bred rage, such a near over powering fury as he had never before. Yet still there had been a hope. He had lived under Lord Stormund’s eye since he had been sent, a bewildered child of eight, to be fostered by the Vacks. Surely his lord knew well what kind of man he was – enough to question their lies!

They had gripped the cross Father Carmon had held, even as he himself had, gave their oath – even as they had done. Then spouted vicious filth. Why had that Cross not burnt their flesh as it was supposed to do?

Then --- they had moved their last and most meaningful piece in their game --- the Damsel Arni. She did not swear, she did not have to. It was plain to all who watch that she came in fear. Her head had lifted, she had stared straight at him, her face became a mask of terror then, with hands up as if to ward off an attack, she had turned and run – assuring all who watched that indeed he was guilty.

He rested his head against the lichen cushioned bark of the fallen tree and starred up at the fraction of sky. There was no he to deal with memory by closing eyes. The castle courtyard held him again he saw the greasy scullion brought from the kitchen to play his part, kneeling to hack the spurs from their owner. The shield with his birth right arms, the black pard, yellow-red eyes carefully depicted to face the foe – was set up against the wall, while those he had been so proud to ride with struck at it in turn with lances until it was dented and the Pard in Pride could no longer be clearly seen.

His sword! – For the first time since he had dropped here he uttered a sound – a moan of one deep wounded. His sword, hammered into shards by the blow’s of the smith’s heaviest tool. Then they had opened path to the great gate of the castle. He, by some strength of pride, had managed to walk that as those about turned their back to him.

The village folk had gathered without. Clots of dung, stones, had rained on him. Somehow he had managed to look straight ahead as if there were no assailants. He had become deaf to the obscenities they had shouted and he could no longer hold the memory until after the forest had swallowed him.

His initial raging anger had died into a sword strong purpose. They had lied, and Lord Stormand had accepted their lies. However that did not mean that any of their twisted words held truth. He was free of Leigh oath – now his life was his to order. Gasping painfully he leaned forward, his forehead supported by crossed arms where those rested on his knees. No longer did his control hold, moisture spilled from his near closed eyes. He willed memory away with all the strength he could summon. This was death of a sort, the death of Huon of Rennay – let it be so!

Mercifully there followed time of darkness. He aroused from that as one comes from a sleep that does not renew, rather leaves one lethargic. The sky overhead was that of night. Then he saw them – the cold jewels of the stars.

“The Sword of Victory!” that constellation was said to have been very visible on his birth night and the midwife had prophesied great things on his behalf because of it.

He laughed harshly. Great things indeed. Yes, he would go down in the rolls of family history – the first knight to be broken of his rank and eternally shamed. Only Huon had been that, and Huon was dead.

The rank smell of his befouled surcoat sickened him. He tore it off. The mail underneath and the quilted nagueton remained. But first water – his mouth was painfully dry.

Somewhere in the wood he heard the pack song of a wolf – the upper branches of the trees about were teased by a breeze, but yet he heard what could be only the gurgle of a stream that he used as a guide, coming out shortly upon the banks of his goal.

He had hunted the great stags in this wooded land and here was the vestiges of a trail which perhaps those mighty creatures had hoof-stamped to reach water.

Stag? He paused in the matter of freeing himself from his mail. Stag, Hart, Buck – the prizes of any hunter. Thus – he, too, might still be hunted – there he was – Hart. A good enough name.

Freed of his befouled and sweat stiffened clothing he drank deeply, from his cupped hands and then stood knee deep in the stream, stooping now and then to bring up harsh sand with which he scrubbed himself thoroughly, nearly drawing blood through the abrazed skin. Somehow he began to feel oddly lighter as if he were free of more than just that grime he rubbed away.

Recognizing a familiar herb within reach he pulled cress and chewed it, forcing himself to swallow the mess as he then grabbed hands full of rough grass to wipe his smarting body. Curtained by the tree’s shadow he dressed, shirt, quilted and padded nagueton, hashed drawers, and boots. But the mail he left lie where it had been dropped when he made his way back to that small clearing.

Settling again in the shadow of the fallen giant he burrowed into the matted leave of seasons. All at once he was tired, as worn as if he had just dismounted after a weary day of riding on some foray.

He fumbled at an inner pocket of a sleeve and brought forth a knife – a sorry weapon indeed but all that was left him. Though if he died under wolf fangs what did it matter now?

Hart Slept.

He dreamed, anguished dreams which wet his body again with fear sweat. Always he faced peril eye to eye in those dreams and yet none of those confrontations he retreated in the last two he had brought down a largely faceless enemy. There came a shriek which was not part of any dream and he awoke to stare up into the sky of mid-morning in time to see a hawk rise into open sight, a struggling furred body in its talons.

Slowly he levered himself up from the mass of molded leaves, aware not only where he was but why. He was going to survive, that oath he sworn within, there was no one to care now but himself. This much he knew and to lock the thought about him as he might again buckle on the discarded mail. He was innocent; the evil lay with them and not him. Therefore he must make it his quest to right his honor by one means or another –

At the edge of the clearing a bush moved. Hart, knife in hand, was on his feet, rimmed by a collar of green leaves a grey head appeared. Wolf! And he, with the fallen trunk behind him, could not flee.

The beast moved forward, it’s attention fixed firmly on him. A spear? He might as well wish for a horse. Yet he gripped the knife firmly, stiffening again as the brush half hiding the wolf shook once more.

Gray as the wolf hide yet showing well above the animal, a fold of cloak swung free as a man pushed through, stumbling into the full open. As did his four footed companion, he stared at Hart. There were many age lines cutting the brown flesh of his face and his hair was a dusky halo of grey-black. However his blue eyes were sharply aware that Hart sensed the knowledge behind them, assessing him.

“You are no hunter!” the wood man spoke in a voice which held castle accent. For all his drab and tattered garb this was no peasant gleaning fallen wood as was the villagers’ right. Nor was there any sight of any weapons, save a knife like into that Hart held, thrust in a battered sheath corded to the length of rope which belted him.

Hart swallowed. There was a needed answer but he could not word it.

“I am Owlglass”, the wolf man broke his too long pause.

“The Hermit?”

“Just so. And whom are you – or perhaps what?”

Hart forced himself to a truthful answer;

“A broken man”, he replied with the name the world now lay upon him. “As for a name – let that of the hunted be mine – Hart”

Owlglass advanced. Cords held a half plump bag to his shoulders. His four-footed companion was gone, once more sucked up brush.

“Out of Gamlin – or Stamglen?” Owlgrass shrugged off his burden. His glaze swept beyond Hart to a yellowish, puffed growth on the downed tree.

There was no need to conceal the truth. “Stamglen.”

With a sudden swing of the knife, he had pulled from his belt the hermit slashed down, slicing the growth from its rooting, twitching it aloft on the point of his blade.

“A lucky day.” He might be addressing Hart or assuring himself. “This is Bloodclear. If there be pus in a wound a decoction of this banishes it.” He resheathed his knife after he tossed his find into the bag. “Now,” he turned his full attention to Hart again. “A broken man – leigeless I presume – and out of Stamglen. I would suspect that you have come afoul of Sir Lazarous.”

Hart Tensed.

Owlglass’s many winkles creased as the man smiled.

“Oh yes, am I astounding you by guessing right? The mighty Champion is well known for tangled games used to rid himself of any hint of a rival.”

“Though,” he seated himself back against the downed tree and a wave of his hand, as if they had met in some hall, he signaled to Hart to join him, “you are young to be swept out of his path in such a permanent fashion. Indeed he must have taken a strong dislike to you.”

Hart could only believe that the hermit knew the shameful manner of his departure from Stamglen. But how – old knowledge? They still told stories of far sight. Also, about Owlglass there were gathered a number of tall tales. Only – unlike his own usage at the castle this man seemed to immediately have seen the source of his trouble.

The hermit turned to rummage again in his bag and bringing out a smaller pouch from which he took a brown cake near the size of his hand, holding it out to Hart.

“Eat.” Making an order of that word.

It was courser than castle bread but tasty. Hart ate. Owlglass produced a second cake, holding it between his teeth as he freed his hands to lift a leathern bottle also from the bag.

Thus, without more words between them, Hart became oddly linked with the man who, as he chewed and swallowed, spoke not of castles or outlawry but rather of the forest. There was something in the flow of words, picturing this and that, which kept the younger man absorbed. His world had vanished; he had come anew into this.

As Owlglass continued, the inhabitants of the new world came and went. Hart watched the great wolf push again out of the bushes and relax himself like a hound, seeming to listen with understanding to the hermit. Squirrels swung down to run along the fallen tree, halting for a breath or two out of time behind the man.

Hart slipped into this new peace, as he had mail. When Owelglass returned the empty packet and bottle to his bag. He was ready to obey a wave of the hermits hand and follow, wolf padding before them.

Now and then the older man stopped to harvest a twist of leaves, a knob of bark gum, each time explaining the service he expected to garner from it. When there came a deep grunting from the underbrush he halted, signaling his companion to do likewise. A snouted head, bearing the curve of wicked tusks, showed. Boar – to face such on foot –!

Owlglass fronted the animal straightly, his hands on his hips as might a sergeant bringing an archer to attention. Though he made no sound the boar snorted and was gone.

“Impudence! That one is getting above himself again.”

Shaking his head the hermit started on again apparently following a well known trail though Hart could see no sign of such.

They came to a downward slope which continued to steepen until one had to catch at a bush for anchorage now and then when boots skidded in the leaf mulch. Here was more light and when they reached level land again Hart could see they were in a gully between half hidden walls. Nor were these natural rocks, but rather had a cutter’s edge to them. Seeing those Hart knew at last the land they were invading.

Those who hunted from Stamglen told dark stories of this and did not ride in this direction. Huon would have hesitated, Hart, having faced what he believed to have been the worst life had to offer, kept on.

On his right the heights were rising, or the road was sinking he could not guess which. Their way curved and he could see beyond the curve a tower one side which must be the cliff itself. Owlglass’s hand fell against a door which could be wood turned stone, entered, then held it for Hart to follow.

What lord or manner of woods runner had caused this to be erected Hart could not guess. Plainly this was how the hermit’s shelter had been for perhaps years. Now it became also his. There were no weapons on the wall, no sign of any need of defense. Beside the fireplace were reed baskets in which lay a treecat, two small kittens pressed against her, a wolf cub with bandaged forepaw and a lemur such as men very seldom saw.

The time which Huon had always known and the duties which had divided his days since childhood no longer existed. In place of the weapons which he had looked for there were ledges protruding from the walls and on those stood books, bound in wood and hide, more than he had ever seen even in Father Camor’s quarters were the Father had had a second duty of tutor to the pages of his lordships sons.

He found himself at school again. Owlglass taught – by day when they traveled the forest ways, by pitchlight from books at night. The hermit gave no reason for taking on a scholar who might have been reluctant. Hart somehow found he did not want to ask why he was here. For his studies built up a wall against the past he had no intention of breaking.

At times they heard sounds of a hunting horn. Then Owlglass took a route which was away from that activity. However one morning he neither changed pace nor direction. Instead he part lifted a curtain of thorned and berried branches so they were under cover but could see a path which was more than just a narrow game trail.

Hart caught the thud of hooves and expected to see hounds and riders appear. It was a white mare that came first into sight, and, clinging to the side saddle clinched about her – Arni. Her coff was gone, her dark hair flying free.

The girl swayed, letting fall reins to clutch at the ribbon braided mane of her mount. She glanced back and uttered a cry close to a whimper, loosed one hand to slap at the mare behind her saddle. The mare reared clearly out of her control. Hart started forward.

In the direction Arni had come a second horse broke cover. The rider a stranger to Hart, a thick shouldered youth whose heavy build suggested he might favor an axe over the sword, though now he held no weapon.

He was grinning, his thick lips parted over yellowish teeth giving him the appearance of some villain born. Yet he was wearing hunting garb of rich yellow-brown stuff and there was a gold scarlet house badge on his breast. He was so close now that that could be read.

A lizard with a crown of horns on its head – the arms of Lord Lazaorus, Champion of Stormont, yet the hunter now reigning his horse to approach Arni at a walk had not appeared in the Champion’s following before Hart’s disgrace.

“Ride, run, whore! You’ll answer for it.” The stranger swung from his horse, now standing quiet as a well trained war mount would, however before he was near enough to seize her, Arni had thrown herself to the ground and was frenziedly rollong herself under the mare.

He flung himself forward to get at her. Only the mare which he ignored shot head forward to bare teeth which closed on his bonnet and some of the hair beneath, flinging both into the air. His hand shot up and he struck the mount between the eyes a blow which even in their hiding place Hart could hear.

The animal backed, shaking her head and sounding something like a scream. One hind hoof was entangled with Arni’s skirt. Having just reach her feet she staggered and went again to hands and feet.

Hart moved, suffering a deep scratch across his jaw as he battled the thorn brush for freedom. There was an ear splitting trumpet, the stranger’s horse, teeth bared in turn, was facing the mare.

His rider paid no attention, instead he grabbed a fistful of Arni’s hair, jerking her up as she screamed.

“No! By the Lady – No!”

Hart moved a pace or two to the left reaching a stand behind the hunter, who was slapping Arni’s face first one side then the other. In Hart’s hand was the knife. He aimed not to kill but disable as he struck down at the hunter’s arm and felt the blade enter flesh, followed by a gush of blood.

A short story by Andre Norton

Copyright ~ Andre-Norton.com

Donated by - Sue Stewart

Duplication (in whole or parts) of this story for profit of any kind NOT permitted.

NOTE: This short story was found in Andre’s files in April of 2015. It is the precursor to the novel Rusted Armor by Andre Norton and Caroline Fike. Neither of which has ever been published anywhere except on this website.

Excerpt from

Rusted Armor

By Andre Norton and Caroline Fike

Chapter One

As the lone figure, clad in the tattered and begrimed remains of a surcoat, moved with aimless, dragging steps into the depths of the forest, none bore witness but tiny denizens of the wilderness. The only eyes observing his collapse at the foot of a moss-coated giant of the wood were those of a curious badger emerging from his set in search of an evening’s foraging. Almost like a frightened child, the man curled in upon himself, as if to ward off blows and passed into the sleep of exhaustion—sleep that carried him into a dream world—a world of things that had been.

***

The light from two tall candles cast a warm glow against the shrine above the solitary young man who knelt before the altar. Shadows painted the surrounding walls like unseen watchers ranked along the loftily vaulted Lady Chapel. Huon imagined witnesses just beyond the range of his senses, gathered to observe his preparations.

He had drawn his sword, grasped it by the blade just below the hilt, holding it before him like a cross. Placing his unadorned helm before the altar he slowly bowed his head. Beneath his long cloak was a simple white linen tunic. The traditional words of the prayer with which he began his vigil came softly to his lips.

“Pure of heart, may I be

Devoted, serving, firstly Thee,

And next all those whose need I see.

So, may I never give a cause

To stain the honor, break the laws

Of those I serve,

From this time forth, without a pause.”

The knightly candidate lapsed into silent contemplation and, as many before him, pondered his life. While the hours marched in silence past his kneeling figure, Huon found himself walking in memory through the days leading up to his vigil. One memory still puzzled him.

It had been on a late autumn afternoon following a particularly difficult passage at arms. The young man had walked out to cool down and let muscles recover from the vigorous action. He thought little of his direction, but wandered along a series of pathways from the training ground, past the kitchens to a sheltered garden he had long ago discovered while on boyhood explorations of the castle grounds. He passed through a low arched gate of woven vines. Huon had earlier marked a small glade beyond, found it a peaceful place where he could rest and think, however this afternoon, to his considerable surprise, it was not so quiet.

He was not alone on that soft autumn afternoon. From a small form huddled on a bench in one corner of the garden had come a low whimper of weeping. He had frozen in mid step, then backed softly away, intent on escape, when the form jerked upward as a slight girl looked to him, her face wet with tears and momentary fear lines etched there. The squire had raised a hand in apology for the intrusion and smiled at the young woman. This was clearly no servant. Her garments were of the finest cut and fabric; even Huon could see that, though seldom did squires associate with such noble guests as those frequenting Stamglen.

“For—forgive me, Lady. I did not mean to intrude.” He had managed to stammer out. She quickly brushed her cheek to hide the evidence of her tears.

“No, don’t go! I know you, Huon of Rennay. I watched you at arms practice, a day gone.” She smiled shyly.

A blush crept unbidden from Huon’s collar. He had no idea his practice had been observed. “Y—you did?”

The girl laughed now, an enchanting sound that seemed to bubble up within her. “I was on the ladies’ balcony that overlooks the practice ground. You were far too busy to notice.”

“Oh,” was all Huon could answer. What to say? He decided that the gallant thing to do was offer assistance worthy of a knight. “Lady, I know not what your difficulty may be, but if I may serve, you need only ask. May I have the privilege of your name?”

His companion looked intently at him for a long moment. “You really mean that! I am Arin, recently of Gamlin. Like you, I am here to further my training.” Then seeming about to add something, she suddenly clapped a hand over her mouth smothering further words. He could do no more than bow and retreat. What had caused such grief in Arin of Gamlin? The question remained and seemed to echo in Huon’s mind as he abruptly came to himself .

The Lady Chapel candles burned steadily, sending ripples of wax to puddle on the stone beside their holders. Suddenly Huon realized that his recollections had wandered in a dangerous direction. He was here on vigil, not to dream of a woman he could never approach in any fashion other than to salute her formally.

Now the candidate prostrated himself before the altar and prayed fervently for power to take his vows with a heart unfettered by any base emotion or motive. In truth, Huon’s greatest desire was to bring honor upon his house, his future knightly order and his lord!

The young man raised his head and stood to his feet, hardly believing the night had passed so swiftly. In moments he would be summoned to the ritual bath and thence to the ceremony toward which his whole young life had been directed, however before he could turn, there struck him from behind such a frigid gust of air that instantly drove life from the great candles. Had there indeed been a witness to his vigil?

Passing his hand over his eyes, Huon shook his head. Long hours of forced wakefulness must be playing tricks with his mind. The morning light that streamed now through the deep-set windows of the chapel penetrated the dusty corners revealing nothing but the silent effigies guarding Stamglen’s ancient dead. The knight candidate turned and paced slowly toward the beckoning day, but as he passed through the nave a sharp sound seemed to burst above him and all familiar surroundings disappeared from his vision.

***

Darkness far deeper than the mere absence of light suddenly cloaked Huon. It was as if he had been plunged from the haven of the holy chapel into a cold and barren space. Reaching out blindly to touch the column that he thought was just before him in the clogging gloom, he stumbled forward.

No longer was there an altar, no longer a stoned flagged chapel floor; Huon found himself in a faintly dawn-lit glade, surrounded by forest, from which strange shadows crept away into hiding. The silence was split by the harsh blast of a horn and he suddenly became aware of the crashing of hooves in the mist behind him. Gripped by confusion, he instinctively lurched forward then, entangling his foot with something in the grass, he sprawled against a dark object looming in his path. Slowly his wits began to clear. The vigil—yes, it was a dream from the past—but now—!

Realizing he had stumbled against bole of a fallen tree, he crouched beside it, looking back just in time to see a mighty hart o’er-leap the log at some distance. Once more the sound that had shattered his dream pierced the air around him—a hunting horn! A pack of coursers, followed by mounted men thundered past in pursuit of the animal. At the fore was—Sir Lazarous! Lazarous—followed by a lovely woman mounted sidesaddle on a silver mare. As they galloped by, unaware of his presence, bitter words broke harshly from Huon’s twisting lips, “Lady of beauty, Lady of lies!”

With all the crushing weight of a ballista’s missile, full memory fell on him, clear now, not as the dreaming of the chapel vigil. Wan light shone in a ragged splotch around him. The forest giant, brought to earth in a spring storm, had borne with it lesser trees, opening a space to the sky. Huon sprawled with his back propped against the fallen trunk. Not far away lay his twisted and be-grimed sword belt. It was this that had entrapped his feet in the gloom. Once again shame and bitter powerlessness enwrapped him.

A stone cut above his eye throbbed painfully, the gift, near to the last, of a villein’s strong and skillful arm. His ragged surcoat stank with clotted dung. Memory once more surged through him, bringing with it all the agony of the hours just past.

At the very first he had felt the confusion and panic of a helplessly trapped beast. Yet still he had clung to hope, for had he not lived under Lord Stormund’s eye since, as a bewildered child of eight the Vacks had taken him in as a fosterling? Surely his lord knew well what sort of man he was—enough to question the lies flung against him!

His accusers had gripped the cross Father Corman held, even as he himself had, had given their oath—even as he did—then spouted vicious filth against him. How could they use a sacred symbol so? Had they sunk so low in their intended evil that all conscience was dead and no truth ritual carried meaning?

Then had come the last and most potent accuser—the Damsel Arin. She did not need to swear; it was plain to all watching that she came in abject fear. Her head had lifted, so that she stared straight at him, her face a mask of terror. Dropping her eyes from his, she spoke in a low but distinct voice, “Yes, that is the man. He did it.” Then, with hands lifted as if to ward off attack, she had turned and run—assuring all assembled in the quadrangle of his guilt.

He rested his head against the lichen-coated bark of the fallen tree and stared up at the fraction of sky. Huon strove to shut out the scene, even as he knew that closing his mind to memory was no way to deal with pain and humiliation. Absently he raised his left hand to the stinging wound on his brow, but before he could touch it, there passed over him a wave of warmth, not from the watery sunlight.

Fool was he to wallow in shame, where none was deserved. He would not cower like a beaten pup and flee again, tail against his hindquarters. No! As he thought back over the agony of the travesty he had endured, a flinty determination began to flower in him. He would be vindicated—and avenged! No matter if it might take a life span of years. Lazarous and his lovely conspirator would pay! Now Huon near reveled in acceptance of that.

The courtyard held him now, the greasy scullion coming from the kitchen to play a part. As the lowest of servants knelt to hack the spurs from his heels, his shield bearing the arms of his birthright, an emerald-eyed black pard rampant against all foes, was propped against a wall. Those, among whom he had proudly served for so short a time, wheeled their mounts and rode with ready lance points well aimed to strike repeatedly until the Pard in Pride was but a dim, much dented outline.

His sword—in spite of the heat of anger, a low moan escaped Huon’s throat, betokening a sorely wounded spirit. The sturdy blade had been smashed into shards by the blows of the smith’s great hammer. Then, as if by a signal, a path straight through the gathered watchers had opened to the great castle gate. By strength of pride alone, Huon had managed to walk out as each of his sworn brothers-in-arms deliberately turned back on him.

The village folk, gathered outside, had rained clots of dung and stones on him. Somehow he was able to gaze straight ahead ignoring their assault. He had willed himself deaf to shouted obscenities and threats until the forest swallowed him.

His raging anger gradually lessened to be replaced with cool purpose. He had been lied against; the greatest of powers had been evoked against him. Lord Stormund had believed a twisted tale of Dark devising. However, Huon was so near to the very edge of the forest, all he needed to do was take the step that would set him in the wilderness. He was free of liege-oath. Now his life was his own to order. Gasping painfully, he leaned forward and supported his forehead on crossed arms where they rested on his knees. At last his control broke and tears he could not withhold spilled from his half-closed eyes. He fought fiercely to suppress the grief of loss, thrust away memory and arouse anger. Very well: the ceremony to break him of his knighthood was death of a sort, the death of Huon of Rennay—then let it be so!

Mercifully shadows enveloped him, bringing a measured sleep. Awakening at last from slumber, un-rested and lethargic, the night sky overhead shone with countless cold, starry jewels.

The Sword of Victory! The star pattern was said to have been visible on his birth night, prompting the midwife to prophesy. She had foreseen great things in his future that night.

He laughed harshly. Great things indeed! Yes, he would go down in the rolls of family history—the first knight to be broken of rank and eternally shamed. Well, Huon had been thus dishonored, but that Huon was now dead.

The rank smell of his befouled surcoat sickened him. He tore it off, leaving the mail and quilted harqueton underneath. Suddenly he realized how thirsty he was; he must have water for his painfully dry throat.

Somewhere out in the wood the pack-song of wolves pierced the night. A light breeze began to tease the crowning branches of the surrounding trees and he could hear the gurgle of a stream. With the inviting sound as a guide, the no-longer-knight soon found its banks.

Huon remembered the great hart that had leapt over the fallen tree. Hart? He paused to free himself of his mail. Hart, stag, buck—prey for any hunter. Humph, he thought, I too, am now the hunted. Why not? I will become “Hart,” a suitable name for a lord-less man.

Freed of his filthy sweat-stiffened clothing, he drank deeply from cupped hands before he waded knee-deep into the stream. He stooped now and again to gather sand from the bottom to scrub thoroughly, almost drawing blood from his abraded skin. Somehow he felt oddly lighter, as though free from more than just rubbed-away grime. Curiously the wound on his brow had ceased to pain him. He felt for it and found not even a scab to mar the skin, but hunger overcame his need to think of that.

Recognizing a familiar plant along the stream’s edge, he pulled some cress and chewed it, forcing himself to swallow. He then tore handfuls of rough grass to dry his smarting body. Curtained by the shadowing trees, he dressed with shirt, quilted and padded harqueton, drawers and boots. But the mail Hart left where he had dropped it and returned to the small clearing.

Settling once more beside the fallen giant, the man burrowed into the leafy litter of countless seasons. All at once he was overcome with such a weariness as would follow a day’s ride on some foray.

The broken knight fumbled at a sleeve pocket and brought out a knife—sorry weapon indeed, but all that had been left him. Though, if he died under wolf fangs, what mattered it now?

Hart slept and as he did he dreamed, anguished dreams that drenched him again with the sweat of fear. Always he came eye-to-eye with peril in those night visions, yet in none of the confrontations did he retreat. The final two nightmares ended in his bringing down a largely faceless enemy. A very real shriek, not of any dream, startled him awake to stare up into the mid-morning sky as a hawk rose into sight with a furred body struggling in its talons.

Slowly Hart levered himself up from the moldy mass of leaves, remembering where he was and why. He would survive—this was his inner oath—with no one to care now but himself. This much he knew, and he locked the thought about him like buckling on the discarded mail. He was innocent; the evil lay with others and not him. Therefore, he must accept his present guise yet struggle to regain what had been ripped from him.

At the edge of the pocket clearing a bush moved. Hart, knife in hand, leapt to his feet. Rimmed by a collar of green leaves, a gray head appeared. Wolf! And he, backed against the massive fallen tree, could not flee.

The beast moved forward, staring fixedly at him. A spear? He might as well wish for a horse; yet he gripped the knife firmly, crouching further as the bush, half hiding the wolf, shook once more.

Gray as the wolf’s hide, but showing well above the animal, a fold of cloak swung free and a man pushed through, stepping fully into the open. As did his four footed companion, he gazed at Hart. Deep age lines creased the brown flesh of his face and his hair was a dusky halo of grayish-black. However his blue eyes were piercingly alert and Hart sensed the wisdom behind them, assessing him.

“You are no hunter,” the woodman spoke in a castle-accented voice. For all his drab and tattered garb, this was no peasant gleaning fallen wood as was the villagers’ right. Nor was there any sign of a weapon, save a knife like to Hart’s, thrust into a battered sheath hanging from the length of rope that belted his waist.

Hart swallowed. An answer was needed, but he could not word one.

“I am Owlglass,” the wolf’s companion finally broke the over-long silence.

“The hermit!”

“Just so. And who are you—or should I ask, what?”

Hart forced himself to a truthful answer. “A broken man,” he replied with the label the world now would lay upon him. “As for a name—let that of the hunter’s prey be mine—Hart.”

Owlglass advanced. Cords fastened a half-filled plump bag to his shoulders. His four footed companion melted once more into the brush.

“Out of Gamlin—or Stamglen?” Owlglass shrugged off his burden. His gaze swept beyond Hart to a yellowish, puffy growth on the downed tree.

There was no need to conceal the truth. “Stamglen.”

With a sudden swing of his knife, the hermit slashed, slicing off a yellow growth rooted onto a dead trunk and twitching it aloft on the tip of his blade.

“A lucky day.” He might be addressing Hart or reassuring himself. “This be Bloodclear. If there is pus in a wound, a decoction of this banishes it.” He re-sheathed his knife after tossing his find into the bag. “Now,” he turned his full attention on Hart again, “a broken man—liegeless I presume—and out of Stamglen. I would suspect that you have come afoul of Sir Lazarous.”

Hart tensed.

Owlglass’s many wrinkles creased into a smile. “Oh, yes, am I astounding you by guessing right? The mighty Champion is well known for weaving tangled games to rid himself of any hint of a rival. Though,” he seated himself back against the downed tree and, with a wave of his hand as might a comrade, well-met in a hall, signaled Hart to join him, “you are young to be swept out of his path so permanently. Indeed he must have taken a strong dislike to you.”

Hart could only believe that the hermit knew the shameful manner of his banishment from Stamglen. But how—old knowledge? Stories were still told of far sight. Also, about the personage of Owlglass there had gathered a number of tall tales. But—unlike his former comrades at the castle this man seemed immediately to recognize the true source of his trouble.

The hermit turned to rummage again in his bag and, bringing out a smaller pouch from which he took a hand-sized brown cake, he offered it to Hart.

“Eat.” He made the word an order.

It was coarser than castle bread but tasty and Hart ate gratefully. Owlglass produced a second cake and, holding it between his teeth to free his hands, lifted a leathern bottle also from the bag.

Thus, without further words between them, Hart became oddly linked with the man who, as he chewed and swallowed, spoke, not of castles or outlawry, but rather of the forest. There was something in that flood of words, picturing many things, which kept the younger man absorbed. His familiar world had vanished; he had come anew into this strange one.

"Rusted Armor"

Copyright ~ Andre-Norton.com

Donated by – Caroline Fike

Formatted by Jay P. Watts aka: “Lotsawatts” ~ May 2015

Duplication (in whole or parts) of this story for profit of any kind NOT permitted.

You can read the manuscript here ~ a donation would be deeply appreciated.