Andre Norton Dies at 93; a Master of Science Fiction

by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt

March 18, 2005 ~ New York Times

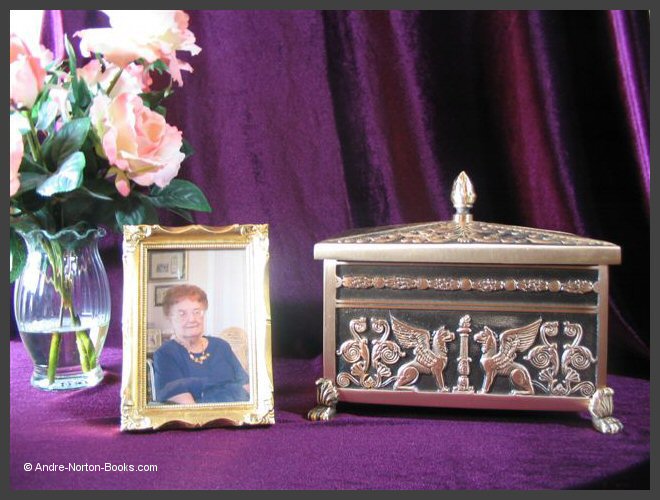

Andre Norton, a prolific and popular science-fiction and fantasy writer whose central theme was the rite of passage to self-realization undertaken by misfits or displaced outsiders, died yesterday at her home in Murfreesboro, Tenn. She was 93.

The cause was congestive heart failure, Sue Stewart, her friend and caretaker, said.

In more than 130 novels, nearly 100 short stories and numerous anthologies that Ms. Norton edited in the science-fiction, fantasy, mystery and western genres, the theme of alienation and return keeps recurring.

In a typical story, "Star Man's Son 2250 A.D." (Harcourt, 1952) - her first science-fiction novel - Fors, a mutant rejected by a postwar society because of his differences, goes in search of a lost city rumored to be free of radiation. Accompanied by a cat with which he communicates telepathically, Fors discovers his own worth through a string of difficult tests.

"Star Man's Son" was the relatively late start of Ms. Norton's science fiction career; until then, she had mainly been a novelist writing juvenile historical fiction and adventure stories, under the pen name Andre Norton, chosen because her readers were thought to be exclusively boys.

At the time, the market for science-fiction was largely confined to magazines, but with the growth of the genre in book form after 1950, Ms. Norton took the field by storm. Donald A. Wollheim, editor of the paperback house Ace Books, saw her potential in an adult market, acquired the rights to "Star Man's Son," published it under the title "Daybreak 2250 A.D.," eliminating all references to the story and its author as being for young readers, and found himself with a steady seller.

Although Ms. Norton's subsequent books for Ace sold in the hundreds of thousands, she found herself the victim of a Catch-22: critics of science fiction did not take her seriously because she was considered a juvenile writer and critics of children's literature dismissed her because she wrote science fiction.

Her legions of readers remained loyal, however, and critics eventually came to take her seriously. She was the first woman to win the Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy award and the Nebula Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement from the Science Fiction Writers of America.

Her work was praised for its unobtrusive depth and complexity. As Francis J. Molson wrote in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, "It is possible that the pace and suspense of Norton's storytelling may so ensnare readers that they may overlook the themes and concerns her narratives embody."

Foremost among those themes, many of her readers have said, was her insistence that personal fulfillment required accepting the individual's contradictions, whether they were sexual, racial or otherwise. For instance, the villains in her most popular series, "Witch World," comprising about 30 volumes, are the females who think falsely that they have to remain virginal to retain their power.

In the same vein, Ms. Norton deplored people's embrace of technology.

"I think the human race made a bad mistake at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution," she told Charles Platt in an interview for his "Dream Makers Volume II: The Uncommon Men and Women Who Write Science Fiction" (1983). "We leaped for the mechanical things."

She added, "People need the use of their hands to feel creative."

Alice Mary Norton, who changed her name legally to Andre Norton in 1934, was born on Feb. 17, 1912, in Cleveland, Ohio, the younger of two daughters of Adalbert Freely Norton, a rug salesman, and Bertha Stemm Norton. At Collingwood High School she wrote for the school newspaper and during her senior year produced her first novel, which, reworked, became her second published book, "Ralestone Luck" (Appleton, 1938).

Intending to become a history teacher, she attended Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve) but was forced to drop out in her freshman year because of the Depression. Taking a job at the Cleveland Public Library, she was assigned to the children's book section, allowing her to become expert in the literature. Though already interested in science fiction, she turned to writing history for young adults, publishing her first novel, "The Prince Commands" (Appleton, 1934), at 22.

Continuing to publish adventure novels, she stayed at the library until 1950, working in 38 of its 40 branches. In 1941, she interrupted that stint to work at the Library of Congress and to own a bookstore in Maryland. In 1950, she took a job as a reader at Gnome Press, the science-fiction publisher, and continued to write on the side. By the time she left, in 1958, to become a full-time writer, she had published 23 novels and several short stories. In the next two decades she wrote almost 70 novels and two dozen short stories, and edited several anthologies. She also collaborated with many writers.

In 1966, she moved to Florida and later to Murfreesboro, where in 1999 she founded High Hallack, a retreat and research library for writers that she closed in 2004.

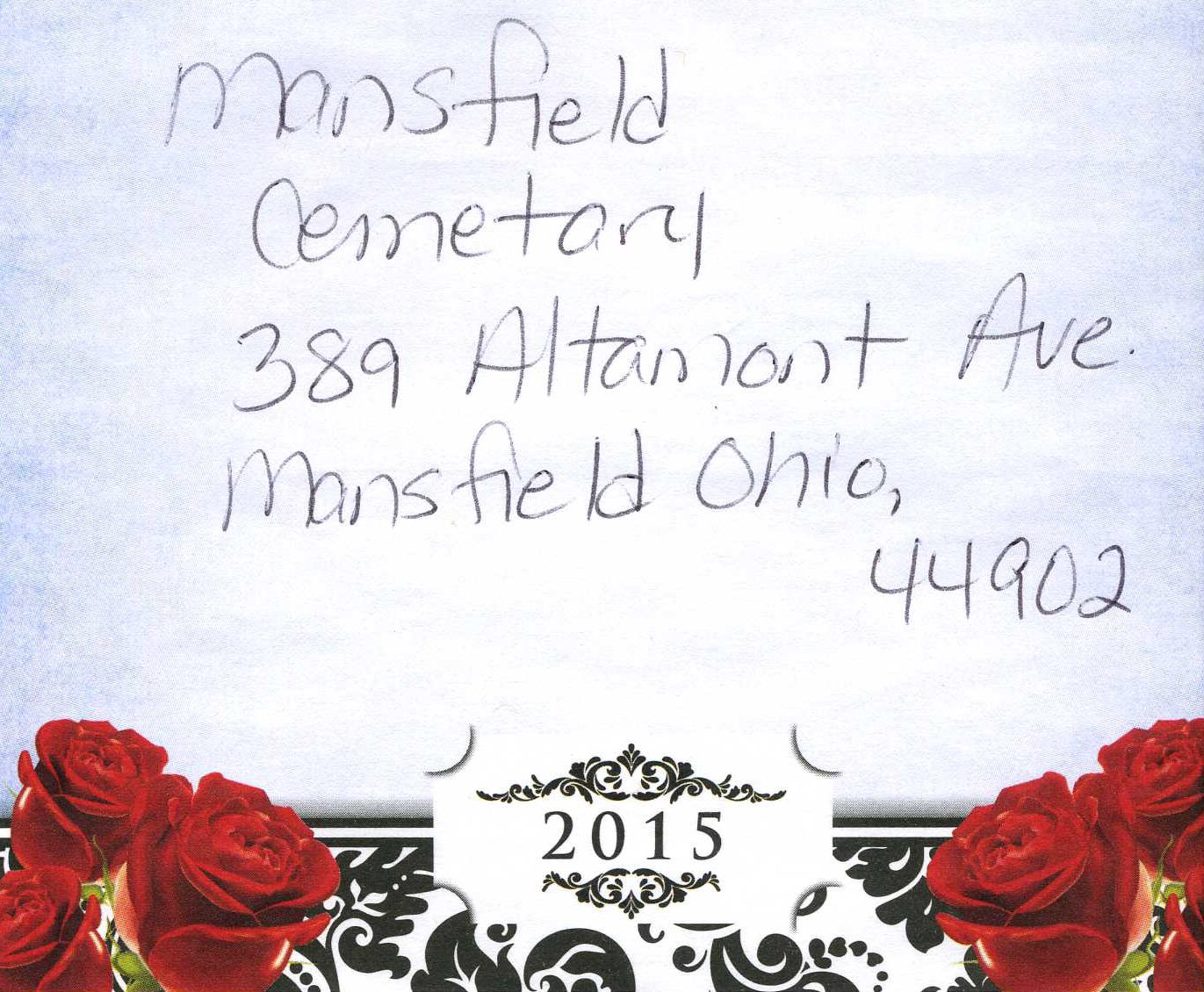

Andre's Grave Site

You are looking for a large 3' cube that says STEMM on it. That is Andre's Mom's headstone. Andre's is directly behind that but with a flat stone.